|

|

|

BRONNEN (ENGELS)

|

|

VIAE

Article by William Ramsay, M.A., Professor of Humanity in the University of Glasgow on pp1191‑1195 of William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D.: A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, John Murray, London, 1875.

VIAE. Three words are employed by the Roman jurists to denote a road, or a right of road, Iter, Actus, Via. The different meanings of these three words are given under Servitutes, p1032.

We next find Viae divided into privatae or agrariae and publicae, the former being those the use of which was free while the soil itself remained private property, the latter those of which the use, the management, and the soil were alike vested in the state. Viae Vicinales (quae in vicis sunt vel quae in vicos ducunt), being country cross-roads merging into the great lines, or at all events not leading to any important terminus, might be either publicae or privatae according as they were formed and maintained at the cost of the state or by the contributions of private individuals (Dig. 43 tit. 8 s.2 §21, 22; tit. 7 s.3; Sicul. Flacc. de Cond. Agr. p9, ed. Goes.). The Viae publicae of the highest class were distinguished by the epithets militares, consulares, praetoriae, answering to the terms ὅδοι βασιλικαὶ among the Greeks and king's highway among ourselves.

That public roads of some kind must have existed from the very foundation of the city is manifest, but as very little friendly intercourse existed with the neighbouring states for any length of time without interruption, they would in all probability not extend beyond the narrow limits of the Roman territory, and would be mere muddy tracks used by the peasants in their journeys to and from market. It was not until the period of the long protracted Samnite wars that the necessity was strongly felt of securing an easy, regular, and safe communication between the city and the legions, and then for the first time we hear of those famous paved roads, which, in after ages, keeping pace with the progress of the Roman arms, connected Rome with her most distant provinces, constituting not only the most useful, but the most lasting of all her works (Strabo, V. p235). The excellence of the principles upon which they were constructed is sufficiently attested by their own extraordinary durability, many specimens being found in the country around Rome which have been used without being repaired for more than a thousand years, and are still in a high state of preservation.

The Romans are said to have adopted their first ideas upon this subject from the Carthaginians (Isidor. XV.16, § 6), and it is extremely probable that the latter people may, from their commercial activity, and the sandy nature of their soil, have p1192been compelled to turn their attention to the best means of facilitating the conveyance of merchandize to different parts of their territory. It must not be imagined, however, that the Romans employed from the first the elaborate process which we are about to describe. The first step would be from the Via Terrena (Dig. 43 tit. 11 s.2), the mere track worn by the feet of men and beasts and the wheels of waggons across the fields, to the Via Glareata, where the surface was hardened by gravel; and even after pavement was introduced the blocks seem originally to have rested merely on a bed of small stones (Liv. XLI.27; compare Liv. X.23, 47)

Livy has recorded (IX.29) that the censorship of Appius Caecus (B.C. 312) was rendered celebrated in after ages from his having brought water into the cityº and paved a road (quod viam munivit et aquam in urbem perduxit), the renowned Via Appia, which extended in the first instance from Rome to Capua, although we can scarcely suppose that it was carried so great a distance in a single lustrum (Niebuhr, Röm. Gesch. III. p356). We undoubtedly hear long before this period of the Via Latina (Liv. II.39), the Via Gabina (Liv. II.11, III.6, V.49), and the Via Salaria (Liv. VII.9), &c.; but even if we allow that Livy does not employ these names by a sort of prolepsis, in order to indicate conveniently a particular direction (and that he does speak by anticipation when he refers to milestones in some of the above passages is certain), yet we have no proof whatever that they were laid down according to the method afterwards adopted with so much success (cf. Liv. VII.39).

Vitruvius enters into no details with regard to road-making, but he gives most minute directions for pavements, and the fragments of ancient pavements still existing and answering to his description correspond so entirely with the remains of the military roads, that we cannot doubt that the processes followed in each case were identical, and thus Vitruvius (VII.1), on the Via Domitiana, will supply all the technical terms.

In the first place, two shallow trenches (sulci) were dug parallel to each other, marking the breadth of the proposed road; this in the great lines, such as the Via Appia, the Via Flaminia, the Via Valeria, &c., is found to have been from 13 to 15 feet, the Via Tusculana is 11, while those of less importance, from not being great thoroughfares, such as the Via which leads up to the temple of Jupiter Latialis, on the summit of the Alban Mount, and which is to this day singularly perfect, seem to have been •exactly 8 feet wide. The loose earth between the Sulci was then removed, and the excavation continued until a solid foundation (gremium) was reached, upon which the materials of the road might firmly rest; if this could not be attained, in consequence of the swampy nature of the ground or from any peculiarity in the soil, a basis was formed artificially by driving piles (fistucationibus). Above the gremium were four distinct strata.• The lowest course was the statumen, consisting of stones not smaller than the hand could just grasp; above the statumen was the rudus, a mass of broken stones cemented with lime (what masons call rubble-work) rammed down hard and •nine inches thick; above the rudus came the nucleus, composed of fragments of bricks and pottery, the pieces being smaller than in the rudus, cemented with lime and •six inches thick. Uppermost was the pavimentum, large polygonal blocks of the hardest stone (silex), usually, at least in the vicinity of Rome, basaltic lava, irregular in form but fitted and jointed with the greatest nicety (apta jungitur arte silex, Tibull. I.7.60) so as to present a perfectly even surface, as free from gaps or irregularities as if the whole had been one solid mass, and presenting much the same external appearances as the most carefully built polygonal walls of the old Pelasgian towns.a The general aspect will be understood from the cut given below of a portion of the street at the entrance of Pompeii (Mazois, Les Ruines de Pompei, vol. I pl. XXXVII).

The centre of the way was a little elevated so as to permit the water to run off easily, and hence the terms agger viae (Isidor. XV.16 §7; Ammian. Marcellin. XIX.16; cf. Virg. Aen. V.273); and summum dorsum (Stat. l.c.), although both may be applied to the whole surface of the pavimentum. Occasionally, at least in cities, rectangular slabs of softer stone were employed instead of the irregular polygons of silex, as we perceive to have been the case in the forum of Trajan, which was paved with travertino, and in part of the great forum under the column of Phocas, and hence the distinction between the phrases silice sternere and saxo quadrato sternere (Liv. X.23, XLI.27). It must be observed, that while on the one hand recourse was had to piling, when a solid foundation could not otherwise be obtained, so, on the other hand, when the road was carried over rock, the statumen and the rudus were dispensed with altogether, and the nucleus was spread immediately on the stony surface previously smoothed to receive it. This is seen to have been the case, we are informed by local antiquaries, on the Via Appia, below Albano, where it was cut through a mass of volcanic peperino.

Nor was this all. Regular foot-paths (margines, Liv. XLI.27, crepidines, Petron. 9; Orelli, Inscrip. n. 3844; umbones, Stat. Silv. IV.3.47) were raised upon each side and strewed with gravel, the different parts were strengthened and bound together with gomphi or stone wedges (Stat. l.c.), and stone blocks were set up at moderate intervals p1193on the side of the foot-paths, in order that travellers on horseback might be able to mount without the aid of an ἀναβόλευς to hoist them up (Plut. C. Gracch. 7). [Stratores]

Finally, C. Gracchus (Plut. l.c.) erected milestones along the whole extent of the great highways, marking the distance from Rome, which appear to have been counted from the gate at which each road issued forth. The passage of Plutarch, however, may only mean that Gracchus erected milestones on the roads which he made or repaired; for it is probable that milestones existed much earlier. [Milliare.] Augustus, when appointed inspector of the viae around the city, erected in the forum a gilded column (χρυσοῦσα μίλιον — χρυσοῦς κίων, milliarium aureum, Dion Cass. LIV.8; Plin. H. N. III.5; Suet. Oth. 6; Tacit. Hist. I.27), on which were inscribed the distance of the principal points to which the viae conducted. Some have imagined, from a passage in Plutarch (Galb. 24), that the distances were calculated from the milliarium aureum, but this seems to be disproved both by the fact that the roads were all divided into miles by C. Gracchus nearly two centuries before, and also by the position of various ancient milestones discovered in modern times (see Holsten. de Milliario Aureo in Graev. Thes. Antiq. Rom. vol. IV and Fabretti de Aquis et Aquaeductis, Diss. III. n. 25).

It is certain that during the earlier ages of the republic the construction and general superintendence of the roads without, and the streets within, the city, were committed like all other important works to the censors. This is proved by the law quoted in Cicero (de Leg. III.3), and by various passages in which these magistrates are represented as having executed important improvements and repairs (Liv. IX.29, 43, Epit. 20, XXII.11, XLI.27; Aurel. Vict. de Viris illust. c. 72; Lips. Excurs. ad Tac. Ann. III.31). These duties, when no censors were in office, devolved upon the consuls, and in their absence on the Praetor Urbanus, the Aediles, or such persons as the senate thought fit to appoint (Liv. XXXIX.2; Cic. c. Verr. I.48, 50, 59). But during the last century of the commonwealth the administration of the roads, as well as of every other department of public business, afforded the tribunes a pretext for popular agitation. C. Gracchus, in what capacity we know not, is said to have exerted himself in making great improvements, both from a conviction of their utility and with a view to the acquirement of popularity (Plut. C. Gracch. 7), and Curio, when tribune, introduced a Lex Viaria for the construction and restoration of many roads and the appointment of himself to the office of inspector (ἐπιστάτης) for five years (Appian, B. C. II.26; Cic. ad Fam. VIII.6). We learn from Cicero (ad Att. I.1), that Thermus, in the year B.C. 65, was Curator of the Flaminian Way, and from Plutarch (Caes. 5), that Julius Caesar held the same office (ἐπιμελητής) with regard to the Appian Way, and laid out great sums of his own money upon it, but by whom these appointments were conferred we cannot tell. During the first years of Augustus, Agrippa, being aedile, repaired all roads at his own proper expense; subsequently the emperor, finding that the roads had fallen into disrepair through neglect, took upon himself the restoration of the Via Flaminia as far as Ariminum, and distributed the rest among the most distinguished men in the state (triumphalibus viris), to be paved out of the money obtained from spoils (ex manubiali pecunia sternendas, Suet. Octav. 30; Dion Cass. LIII.22). In the reign of Claudius we find that this charge had fallen upon the quaestors, and that they were relieved of it by him, although some give a different interpretation to the words (Suet. Claud. 24). Generally speaking, however, under the empire, the post of inspector-in‑chief (curator), — and each great line appears to have had a separate officer with this appellation, — was considered a high dignity (Plin. Ep. V.15), insomuch that the title was frequently assumed by the emperors themselves, and a great number of inscriptions are extant, bearing the names of upwards of twenty princes from Augustus to Constantine, commemorating their exertions in making and maintaining public ways (Gruter, Corp. Inscrip. cxlix . . . . . clix).

These curatores were at first, it would appear, appointed upon special occasions, and at all times must have been regarded as honorary functionaries rather than practical men of business. But from the beginning of the sixth century of the city there existed regular commissioners, whose sole duty appears to have been the care of the ways, four (quattuorviri viarum) superintending the streets within the walls, and two the roads without (Dig. 1. tit. 2 s.2 §30 compared with Dion Cass. LIV.26). When Augustus remodelled the inferior magistracies he included the former in the vigintivirate, and abolished the latter; but when he undertook the care of the viae around the city, he appointed under himself two road-makers (ὁδοποιοῦς, Dion Cass. LIV.8), persons of praetorian rank, to whom he assigned two lictors. These were probably included in the number of the new superintendents of public works instituted by him (Suet. Octav. 37), and would continue from that time forward to discharge their duties, subject to the supervision and control of the curatores or inspectors-general.

Even the contractors employed (mancipes, Tacit. Ann. II.31) were proud to associate their names with these vast undertakings, and an inscription has been preserved (Orell. Inscrip. n. 3221) in which a wife, in paying the last tribute to her husband, inscribes upon his tomb Mancipi Viae Appiae. The funds required were of course derived, under ordinary circumstance, from the public treasury (Dion Cass. LIII.22; Sicul. Flacc. de cond. agr.p9, ed. Goes.), but individuals also were not unfrequently found willing to devote their own private means to these great national enterprises. This, as we have already seen, was the case with Caesar and Agrippa, and we learn from inscriptions that the example was imitated by many others of less note (e.g. Gruter, clxi. n. 1 and 2). The Viae Vicinales were in the hands of the rural authorities (magistri pagorum), and seem to have been maintained by voluntary contribution or assessment, like our parish roads (Sicul. Flacc. p9), while the streets within the city were kept in repair by the inhabitants, each person being answerable for the portion opposite to his own house (Dig. 43 tit. 10 s.3).

Our limits preclude us from entering upon so large a subject as the history of the numerous military roads which intersected the Roman dominions. We shall content ourselves with simply mentioning those which issued from Rome, together with their p1194most important branches within the bounds of Italy, naming at the same time the principal towns through which they passed, so as to convey a general idea of their course. For all the details and controversies connected with their origin, gradual extension, and changes, the various stations upon each, the distances, and similar topics, we must refer to the treatises enumerated at the close of this article, and to the researches of the local antiquaries, the most important of whom, in so far as the southern districts are concerned, is Romanelli.

Beginning our circuit of the walls at the Porta Capena, the first in order, as in dignity, is,

I. The Via Appia, the Great South Road. It was commenced, as we have already stated, by Appius Claudius Caecus, when censor, and has always been the most celebrated of the Roman Ways. It was the first ever laid down upon a grand scale and upon scientific principles, the natural obstacles which it was necessary to overcome were of the most formidable nature, and when completed it well deserved the title of Queen of Roads (regina viarum, Stat. Silv. II.2, 12). We know that it was in perfect repair when Procopius wrote (Bell. Goth. I.14), long after the devastating inroads of the northern barbarians; and even to this day the cuttings through hills and masses of solid rock, the filling up of hollows, the bridging of ravines, the substructions to lessen the rapidity of steep descents, and the embankments over swamps, demonstrate the vast sums and the prodigious labour that must have been lavished on its construction. It issued from the Porta Capena, and passing through Aricia, Tres Tabernae, Appii Forum, Tarracina, Fundi, Formiae, Minturnae, Sinuessa, and Casilinum, terminated at Capua, but was eventually extended through Calatia and Caudium to Beneventum, and finally from thence through Venusia, Tarentum, and Uria, to Brundisium.

The ramifications of the Via Appia most worthy of notice, are:

The Via Setina, which connected it with Setia. Originally it would appear that the Via Appia passed through Velitrae and Setia, avoiding the marshes altogether, and travellers, to escape this circuit, embarked upon the canal, which in the days of Horace traversed a portion of the swamps.

The Via Domitiana struck off at Sinuessa, and keeping close to the shore passed through Liternum, Cumae, Puteoli, Neapolis, Herculaneum, Oplontiº, Pompeii, and Stabiae to Surrentum, making the complete circuit of the bay of Naples.

The Via Campana or Consularis from Capua to Cumae sending off a branch to Puteoli and another through Atella to Neapolis.

The Via Aquillia began at Capua and ran south through Nola and Nuceria to Salernum, from thence, after sending off a branch to Paestum, it took a wide sweep inland through Eburi and the region of the Mons Alburnus up the valley of the Tanager; it then struck south through the very heart of Lucania and Bruttium, and passing Nerulum, Interamnia and Cosentia, returned to the sea at Vibo, and thence through Medma to Rhegium. This road sent off a branch near the sources of the Tanager, which ran down to the sea at Blanda on the Laus Sinus and then continued along the whole line of the Bruttian coast through Laus and Terina to Vibo, where it joined the main stem.

The Via Egnatia began at Beneventum, struck north through the country of the Hirpini to Equotuticum, entered Apulia at Aecae, and passing through Herdonia, Canusium, and Rubi, reached the Adriatic at Barium and followed the coast through Egnatia to Brundusium. This was the route followed by Horace.º It was doubtful whether it bore the name given above in the early part of its course.

The Via Trajana began at Venusia and ran in nearly a straight line across Lucania to Heraclea on the Sinus Tarentinus, thence following southwards the line of the east coast it passed through Thurii, Croto, and Scyllacium, and completed the circuit of Bruttium by meeting the Via Aquillia at Rhegium.

A Via Minucia is mentioned by Cicero (ad Att. IX.6), and a Via Numicia by Horace (Epist. I.18.20),º both of which seem to have passed through Samnium from north to south, connecting the Valerian and the Aquillian and cutting the Appian and the Latin ways. Their course is unknown. Some believe them to be one and the same.

Returning to Rome, we find issuing from the porta Capena, or a gate in its immediate vicinity:

II. The Via Latina, another great line leading to Beneventum, but keeping a course farther inland than the Via Appia. Soon after leaving the city it sent off a short branch (Via Tusculana) to Tusculum, and passing through Compitum Anagninum, Ferentinum, Frusino, Fregellae, Fabrateria, Aquinum, Casinum, Venafrum, Teanum, Allifae, and Telesia, joined the Via Appia at Beneventum.

A cross-road called the Via Hadriana, running from Minturnae through Suessa Aurunca to Teanum, connected the Via Appia with the Via Latina.

III. From the Porta Esquilina issued the Via Labicana, which passing Labicum fell into the Via Latina at the station ad Bivium 30 miles from Rome.

IV. The Via Praenestina, originally the Via Gabina, issued from the same gate with the former. Passing through Gabii and Praeneste, it joined the Via Latina just below Anagnia.

V. Passing over the Via Collatina as of little importance, we find the Via Tiburtina, which issued from the Porta Tiburtina, and proceeding N.E. to Tibur, a distance of about 20 miles, was continued from thence, in the same direction, under the name of the Via Valeria, and traversing the country of the Sabines passed through Carseoli and Corfinium to Aternum on the Adriatic, thence to Adria, and so along the coast to Castrum Truentinum, where it fell into the Via Salaria.

A branch of the Via Valeria led to Sublaqueum, and was called Via Sublacensis. Another branch extended from Adria along the coast southwards through the country of Frentani to Larinum, being called, as some purpose, Via Frentana Appula.

VI. The Via Nomentana, anciently Ficulnensis, ran from the porta Collina, crossed the Anio to Nomentum, and a little beyond fell into the Via Salaria at Eretum.

VII. The Via Salaria, also from the porta Collina (passing Fidenae and Crustumerium) ran north and east through Sabinum and Picenum to Reate and Asculum Picenum. At Castrum Truentinum it reached the coast, which it followed until it joined the Via Flaminia at Ancona.

VIII. Next comes the Via Flaminia, the Great North Road commenced in the censorship of C. Flaminius and carried ultimately to Ariminum. p1195It issued from the Porta Flaminia and proceeded nearly north to Ocriculum and Narnia in Umbria. Here a branch struck off, making a sweep to the east through Interamna and Spoletium, and fell again into the main trunk (which passed through Mevania) at Fulginia. It continued through Forum Flaminiiº — and Nuceria, where it again divided, one line running nearly straight to Fanum Fortunae on the Adriatic, while the other diverging to Ancona continued from thence along the coast to Fanum Fortunae, where the two branches uniting passed on to Ariminum through Pisaurum. From thence the Via Flaminia was extended under the name of the Via Aemilia and traversed the heart of Cisalpine Gaul through Bononia, Mutina, Parma, Placentia (where it crossed the Po) to Mediolanum. From this point branches were sent off through Bergomum, Brixia, Verona, Vicentia, Patavium and Aquileia to Tergeste on the east, and through Novaria, Vercelli, Eporedia and Augusta Praetoria to the Alpis Graia on the west, besides another branch in the same direction through Ticinum and Industria to Augusta Taurinorum. Nor must we omit the Via Postumia, which struck from Verona right down across the Apennines to Genoa, passing through Mantua and Cremona, crossing the Po at Placentia and so through Iria, Dertona and Libarna, sending off a branch from Dertona to Asta.

Of the roads striking out of the Via Flaminia in the immediate vicinity of Rome the most important is the Via Cassia, which diverging near the Pons Mulvius and passing not far from Veii traversed Etruria through Baccane, Sutrium, Vulsinii, Clusium, Arretium, Florentia, Pistoria, and Luca, joining the Via Aurelia at Luna.

(α) The Via Amerina broke off from the Via Cassia near Baccanae, and held north through Falerii, Tuder, and Perusia, re-uniting itself with the Via Cassia at Clusium.

(β) Not far from the Pons Mulvius the Via Clodia separated from the Via Cassia, and proceeding to Sabate on the Lacus Sabatinus there divided into two, the principal branch passing through central Etruria to Rusellae and thence due north to Florentia, the other passing through Tarquinii and then falling into the Via Aurelia.

(γ) Beyond Baccanae the Via Cimina branched off, crossing the Mons Ciminus and rejoining the Via Cassia near Fanum Voltumnae.

IX. The Via Aurelia, the Great Coast Road, issued originally from the Porta Janiculensis and subsequently from the Porta Aurelia. It reached the coast at Alsium and followed the shore of the lower sea along Etruria and Liguria by Genoa as far as Forum Julii in Gaul. In the first instance it extended no farther than Pisa.

X. The Via Portuensis kept the right bank of the Tiber to Portus Augusti.

XI. The Via Ostiensis originally passed through the Porta Trigemina, afterwards through the Porta Ostiensis, and kept the left bank of the Tiber to Ostia. From thence it was continued under the name of Via Severiana along the coast southward through Laurentum, Antium, and Circaei, till it joined the Via Appia at Tarracina. The Via Laurentina, leading direct to Laurentum, seems to have branched off from the Via Ostiensis at a short distance from Rome.

XII. Lastly, the Via Ardeatina from Rome to Ardea. According to some this branched off from the Via Appia.

The most elaborate treatise upon Roman roads is Bergier, Histoire des Grands Chemins de l'Empire Romain, published in 1622. It is translated into Latin in the tenth volume of the Thesaurus of Graevius, and with the notes of Henninius occupies more than 800 folio pages. In the first part of the above article the essay of Nibby, Delle Vie degli Antichi dissertazione, appended to the fourth volume of the fourth Roman edition of Nardini, as been closely followed. Considerable caution, however, is necessary in using the works of this author, who although a profound local antiquary, is by no means an accurate scholar. To gain a knowledge of that portion of the subject so lightly touched upon at the close of the article, it is necessary to consult the various commentaries upon the Tabula Peutingeriana and the different ancient Itineraries, together with the geographical works of Collarius, Cluverius, and D'Anville.

Bron: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Viae.html |

|

|

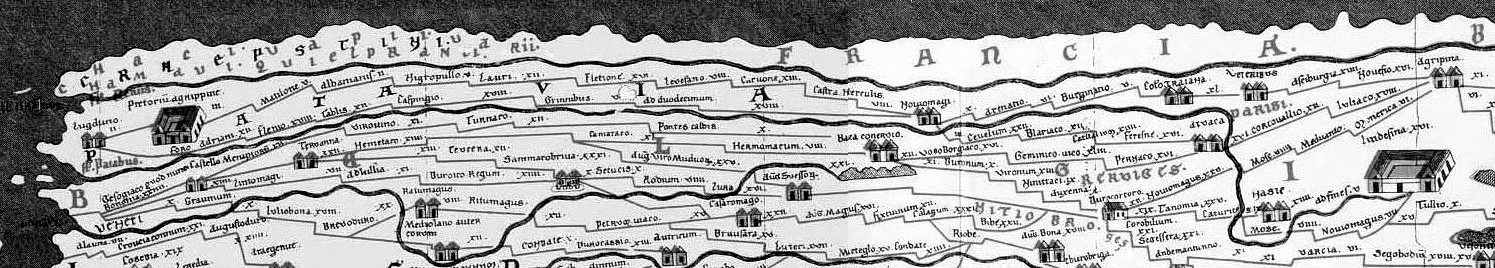

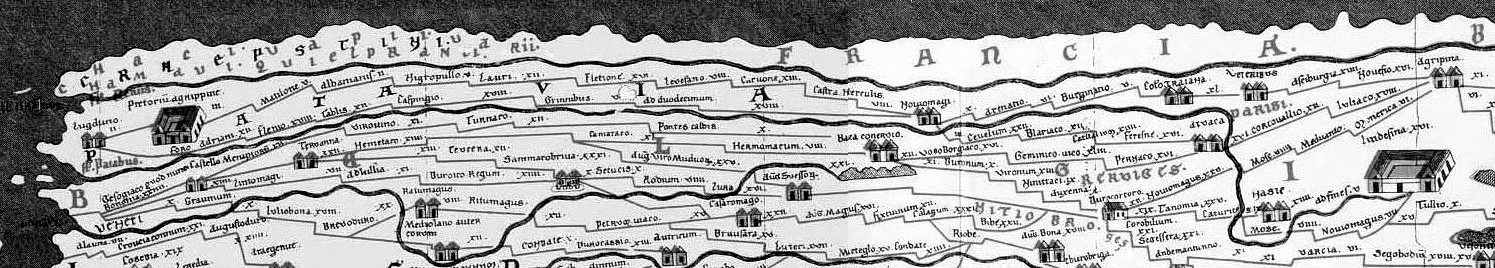

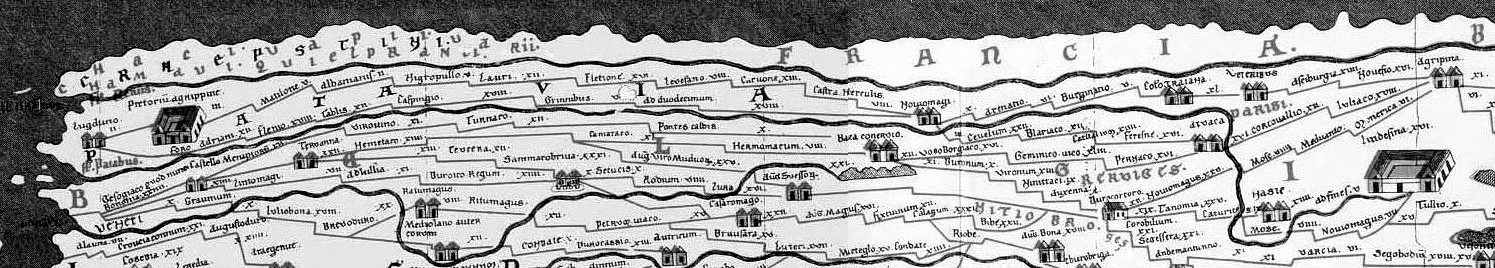

CARTOGRAPHIC IMAGES

DESCRIPTION: Shown here are reproductions of an early road map of the imperial highways of the Roman world, covering the area roughly from southeast England to present day Sri-Lanka. It is not a 'map' in the true sense of the word, but a cartogram. No copies of the original have survived but a copy of it, now in Vienna, was purportedly made in 1265 by a monk at Colmar who fortunately contented himself with adding a few scriptural names, and who seems to have omitted nothing important that appeared in the original. The entire map was originally a long, narrow parchment roll and in its present state measures 22 feet,1.75 inches long by 13.25 inches wide (6.75 meters long but only 34 centimeters wide). Only one of these 'original' twelve section is now lost. According to most authorities, about A.D. 250 the original tables were, themselves, copied from a larger original map of the first century A.D. (some scholars have identified that the author may have used M.V. Agrippa's world map as his source (Slide#118). About A.D. 350 the presentation of the coastal regions was improved and some islands were added. At the turn of the 5th-6th centuries the world ocean was added and improvements were made to the seas; at about the same time, the influence of this map appears in a work by an anonymous cosmographer of Ravenna, who made use of some new material recently added to his source. Since the Ravenna cosmographer names a certain Castorius as the author of his source in connection with material also found in the Tabula Peutingeriana, it is to be inferred that this was the maker's name for the original. The overall form of the Colmar edition, which is the basic form of the Tabula as it has reached us today, must have been fixed at this period, about A.D. 500; although a few local corrections were made subsequently, for example, in the 8th and 9th centuries. This Colmar copy was found by Konrad Celtes (1459-1508), a German poet and scholar for the Emperor Maximilian I and later turned over to Konrad Peutinger (1465-1547) in 1508 in Augsburg and has since been known as the Tabula Peutingeriana or Peutinger Tables or Itineraries. After Peutinger's death, two of the twelve sections of the Colmar manuscript were engraved and published in 1591 with annotated text and place-names taken from the sections reproduced. A second edition by Abraham Ortelius was published in Antwerp in 1598 as part of his Theatri Orbis Terrarum Parergon which contained eight of the twelve sections of the Table. Numerous other engraved reproductions were made until 1753 when it was finally reproduced in its entirety. In its design, the Peutinger Table makes no pretense of showing the whole world or even its major parts in correct proportion. It is merely a graphic compendium of mileages or basically an itinerary route map with the roads delineated predominantly by straight lines, often with curious jogs. The routes are drawn in red, while the sea is indicated by greenish-blue. The map does not conform to the rules of any projection, nor is it possible to apply a constant scale to determine distances from place to place; for these measurements we have to refer to the figures written in by the author. Also the Table was not apparently designed for military use, but instead gives prominence to trading centers, mineral springs, places of pilgrimage, mountain chains (in profile) and in three great cities (Rome, Constantinople and Antioch) set three rulers, believed to represent the sons of Constantine enthroned as symbols of a tripartite empire. The use of vignettes and/or medallions is also found depicting the city of Alexandria, while smaller towns are illustrated by little houses; three forest districts, two in Germany and one in Syria, are represented by sketches of trees. Except for a very few instances, where the interpolation may be easily traced, there is nothing in the Peutinger Table which has any reference to a time later than Diocletian; and the greater number of the names it contains may be referred to an era earlier than the death of Augustus in A.D. 14. The arrangement of the barbarian tribes on the frontiers of the Empire seems to agree pretty nearly with what we know of them in the reign of Marcus Aurelius; and the importance of the name of Persia, for instance, in the far East, perhaps points to a revision of this part of the Table as late as the 3rd century, at some time subsequent to the great Persian revival of A.D. 226 - but these details leave the essential character of the plan strictly classical. In the Jansoon edition of the Peutinger Table (1652), the first sheet shows a section of southeastern England protruding from the title cartouche, with the roads and harbors marked. France, Spain, and North Africa with roads, cities and some prominent buildings are also depicted, along with major Mediterranean islands being Corsica and Sardinia. The second page, comprising Segments III and IV, shows Italy with surrounding islands and landforms bordering adjacent seas. Special prominence is given to Rome, with many roads leading to it, of course. A royal figure, probably a Pope, or perhaps an allegory of Christ the King is portrayed as representative of the city along with a building which resembles St. Peters Basilica (or the personage could be that of one of Constantine's sons as previously mentioned). Further south is the city of Naples drawn inland, next to it is a dark mound which might represent the buried cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Segments V and VI illustrate the eastern Mediterranean by prominently showing the Grecian archipelago and present-day Turkey and Crete. The seventh Segment shows Cyprus, present-day Saudi Arabia, a large allegorical representation of the Holy City, and the area southeast to Mesopotamia. The last, or eighth Segment depicts Babylon to the Caspian Sea, the Indian peninsula and, in the bottom right corner, the island of Taprobane, the Ptolemaic name for Ceylon/Sri Lanka. The Colmar manuscript of the Peutinger Tables, also known as Codex Vindobonensis 324, is presently in the National Bibliothek, Vienna and has been divided into sections for preservation. Its date of transcription is 12th or early 13th century, but it has long been recognized as a copy of an ancient map. In his will of 1508, the humanist Konrad Celtes of Vienna left to Konrad Peutinger (in whose hands it had been since the previous year) what he called Itinerarium Antonini. This was not justified as a title: it is indeed a road map, but not connected with the Antonine emperors and different from the Antonine Itineraries. It was first published in 1591 by Markus Welser, a relative of the Peutingers and since 1618 n has generally been known as the Tabula Peutingeriana or translations of that phase. Tabula is one Latin word for map, but forma is more common. Inexplicably the word tabula has been translated "table" rather than "picture" or "map" in popular usage. It is now time to call it the "Peutinger Map" to avoid any misconception that the original image was somehow carved on a table or was like a statistical table. The alternative naming of the Peutinger Map as the "world map of Castorius" has met with very little support. Castorius, a geographical writer of the 4th century A.D., is several times mentioned as a source in the Ravenna cosmography; but there is no evidence to link him directly with the Peutinger Map. The original roll at the time of its transcription in the early Middle Ages was of eleven sheets, but as such it was incomplete, since much of Britain, Spain,and the western part of North Africa were already missing at the time of copying; there may also have been an introductory sheet forming part of an earlier prototype version. It was evidently not, as was once thought, the work of the Dominican monk Konrad of Colmar, who in 1265 quite independently produced a mappamundi that he says he copied onto twelve parchment pages; the paleography suggests an earlier date. The second sheet of the Peutinger Map was treated as if it had been the first, with spellings of truncated names containing false initial capitals (for example, Ridumo for what was originally Moriduno). Hence a total of twelve sheets extant at the time of copying can be accounted for only by assuming that, when the copyist mentioned this number, he was including a title sheet. The Peutinger Map was primarily drawn to show main roads, totaling some 70,000 Roman miles (104,000 km), and to depict features such as staging posts, spas, distances between stages, large rivers, and forests (represented as groups of trees). It is not a military map, though it could have been used for military purposes but the words of Vegetius give an indication of its possible function. They suggest that, whether or not the term itinerarium pictum [painted itinerary], was in current use, it is a convenient phrase for this unique map. The distances are normally recorded in Roman miles, but for Gaul they are in leagues, for Persian lands in parasangs, and for India evidently in Indian miles. The proportions of the Peutinger Map are such that distances east-west are represented at a much larger scale than distances north-south; for example, Rome looks as though it were nearer to Carthage than Naples is to Pompeii. The archetype may well have been on a papyrus roll, designed for carrying around in a capsa [tool box]. As such, its width would be severely limited, whereas its length would not. In the extant map a north-south road tends to appear at only a slightly different angle from an east-west one, and distances are calculated not by the map's scale but by adding up the mileages of successive staging posts. The date of the archtype is likely to have been between A.D. 335 and 366. Such dating is suggested by the three personifications placed on Rome, Constantinople (labeled Constantinoplis, not Byzantium ) and Antioch; and it fits in well enough with biblical references on the map. Sometime after the foundation of Constantinople in A.D. 330 as a new Rome on the site of Byzantium, Antioch was recognized as the important bastion against the Parthians. Put the suggestion that this 4th century archetype was based on a much earlier map would account for the inclusion of Herculaneum, Oplontis, and Pompeii, which had been destroyed in the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79 and not rebuilt, except for parts of Pompeii. It is also perhaps easier, on this supposition, to see why certain roads are omitted, such as the major routes through the Parthian empire mentioned in the Mansiones Parthicæ [Parthian Stations] of Isidorus of Charax. This work is believed to have been compiled in the late first century A.D. Around the personification of Rome - a female figure on a throne holding a globe, a spear, and a shield - are twelve main roads, each with its name attached, a practice not adopted elsewhere. The Tiber is correctly shown with 90 percent of the city on its left bank. But owing to the personification the city surround is formally shown as a circle, enlarged in proportion to the very narrow width of the Italian peninsula. The Via Triumphalis is indicated as leading to a church of Saint Peter; the words ad scm [sanctum] Petrum are given in large minuscules on the medieval copy. Ostia is shown with a harbor occupying about one-third of a circle, in a fashion similar to that of miniatures in the early manuscripts of Virgil's Aeneid. Constantinople is represented by a helmeted female figure seated on a throne and holding in her left hand a spear and a shield. Nearby is a high column (rather than a lighthouse) surmounted by the statue of a warrior, presumably Constantine the Great . Antioch has a similar female personification, perhaps originating in a statue of the Tyche [fortune] of the city, together with arches of an aqueduct or possibly of a bridge. Nearby is the park of Daphne, dedicated to Apollo and other gods and famous for its natural beauty and as a leisure center. Even though the temple of Apollo was burned down in 362, there were many other temples, so that this is not necessarily a guide to the dating. It has been claimed that in A.D. 365-66 all three personified cities were important, since the pretender Procopius had his seat of power in Constantinople, Valentinian I in Rome and his brother Valens in Antioch. But in fact, although Valens set out for Antioch, he was diverted to fight Procopius and he cannot be correctly associated with the last-named city. Throughout the map, mountains are marked in pale brown and principal rivers in green. Names of countries and some tribes are recorded. Apart from the personifications, cartographic signs include representations of harbors, altars, granaries, spas, and settlements. A unique sign is that for a tunnel, used for the Crypta Neapolitiana, near Pozzuoli. Harbors, if indicated, are given the accurate shape mentioned in connection with Ostia. The sign for a spa is an ideogram of a roughly square building with an internal courtyard, often with a gabled tower at each end of the near side. There are fifty-two such buildings represented, of which twenty-eight are at places specifically called Aquae; in some other cases there is reason to think that a place so denoted had prominent baths. There are also in the Peutinger Map places with cartographic signs for granaries, denoted as rectangular roofed buildings. One such is Centumcellæ [Civitavecchia], which had a corn-importing harbor of some size. Variants of a two-gabled building were used to depict some settlements, but most were distinguished by no more than a name. Attempts to differentiate between types of settlements on the map and to establish criteria for the attribution of signs have not been entirely successful. Certain important cities are shown with walls: Aquileia, Ravenna, Thessalonica [Salonika], Nicæa [Iznik], Nicomedia and Ancyra. But why would the triple-gable sign appear only at Forum Iulii [Frejus], Augusta Taurinorum [Turin], Luca [Lucca], Narona [on the Neretva River], and Tomis [Constanta]? It is interesting to see that, just as there is one personification in the West and two in the East, so two cities of the second rank, symbolically given walls, are in the West and four in the East. Important cities like Carthage, Ephesus, and Alexandria are not shown with a distinctive sign. The road network is thought to have been based (at least within the empire) on information held by the cursus publicus, responsible for organizing the official transport system set up by Augustus. This system, extended under the late empire to troop movements, relied very largely on staging posts at more or less regular intervals; couriers traveled an average of fifty Roman miles (74 km) a day. The part of the British section of the Peutinger Map that survives is so fragmentary that it covers only a limited area of the southeast, not even including London, and an even smaller area around Exeter. Colchester, surprisingly, is given no cartographic sign. The most northerly place extant in Britain appears as Ad Taum; but it is very far removed from the river Tay. This name, however, really consists of the ends of [Ven]ta [Icenor]um (Caistor Saint Edmund, Norwich), and the only unusual feature is ad, which may have belonged to an adjacent name. One of the important features of the map is that it records so many small places. This can be well illustrated by a name in Italy otherwise recorded only (in corrupt form) in the Ravenna cosmography. On the Gulf of Naples, marked as being six Roman miles from Herculaneum and three miles each from Pompeii and Stabiae [Castellammare di Stabia ], is shown a large building with the name Oplont[i]s. Until recently scholars could not place this name, like a number of others. But since 1964 a large palace, which probably belonged to Nero's empress Poppæa, has been excavated at Torre Annunziata, and it seems to authenticate the detail on the map. Or again, a much earlier discovery near Aquileia in 1830 appears to correspond to an entry on the Peutinger Map. A large bathing establishment, mentioned also by the elder Pliny, was discovered on the lower reaches of the river Isonzo. This is probably the place given the cartographic sign for a spa, with the words Fonte Timavi [spring of the river Timavus]. Its fresh waters by the sea were regarded as an unusual phenomenon and obviously worth mapping. Owing to the shape of the map, the Nile could not be represented as a long river if it were made to flow northward throughout its course. Instead it is made to rise in the mountains of Cyrenaica and to flow "eastward" to a point just above the delta. The delta itself is shown in less compressed form from south to north than most parts of the Peutinger Map. The distributaries of the Nile are shown to have many islands, three of them marked with temples of Serapis, three with temples of Isis, while the roads are somewhat discontinuous. On the Sinai desert we find the words desertum ubi quadraginta annis erraverunt filii Israelis ducente Moyse [the desen where the children of Israel wandered for forty years guided by Moses], and there are other biblical references. There is also an area in central Asia labeled Hic Alexander responsum accepit usq[ue] quo Alexander [Here Alexander was given the oracular reply: "How far, Alexander?"]. Perhaps these ample descriptions, whether Christian or pagan, were added on otherwise empty space about the 5th or 6th century A.D. In several areas research is in progress combining fieldwork with study of the Peutinger Map and of the history of place-names. One such is the area between the Gulf of Aqaba and Damascus.

LOCATION: Österreichische National Bibliothek, Vienna

REFERENCES:

Bagrow, L., The History of Cartography, pp. 37-38.

Beazley, C., The Dawn of Modern Geography, vol. I; pp. 381-383.

Bricker, C., Landmarks in Mapmaking, pp. 21-22.

Brown, L., The Story of Maps, pp. 54; 92-93.

Brown, L.A., The World Encompassed, No. 5.

Dilke, O.A.W., Greek and Roman Maps, pp. 112-120, 128, 152-3, 158-9, 169-70, 193-5.

Harley, J.B., The History of Cartography, Volume One, pp. 238-242., Plate 5

Nebenzahl, K., Maps of the Holy Lands, pp. 20-23, Plate 4 (color)

Nordenskiöld, A.E., Facsimile Atlas, p.35.

Jansoon, Tabula Itineraria ex illustri Peutingerorum Bibliotheca quae Mugistae Vindelicorum beneficio Marci Velseri SeptemVeri Augustani in lucem edita,1741.

*illustrated

A portion of the Peutinger Map: Western Asia Minor and Egypt. The elongated deformation of the map is shown by the ribbon-like representation of (top-to-bottom) the Gulf of Azov and the Black, Aegean, Mediterranean, and Red Seas. Constantinople is named as such and not as"Byzantium", which confirms the pre-5th century date of the archetype. Its personification is in the form of a female warrior, enthroned with a shield and spear. Close by are a column and a statue, presumably of Constantine the Great. (original size: 33 X 56. cm)

Bron:

http://cartographicimages.net/Cartographic_Images/120_Peutinger_Table.html

|

|

|

A Forgotten Masterpiece of Cartography for Roman Historians: Pierre Lapie’s Orbis Romanus ad Illustranda Itineraria (1845)

Richard Talbert

All of Tony Birley’s Roman emperors – Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius, Septimius Severus – were great travelers, and it is abundantly obvious from his writing that he delights in tracing their movements. In each of the three biographies, the Geographical Index is an invaluable aid to the reader, therefore. Not surprisingly, by far the longest Geographical Index is in Hadrian: The Restless Emperor (1997), extending almost ten pages from Abae – “little Abae in Phocis” (186) – to the Zilchi.1 For modern scholars to gain the appropriate geographical perspective, maps are naturally essential; but it is notorious that adequate provision of them to cover the vast span of the Roman empire in all its complexity has always been a source of special difficulty. How poignant it is, therefore, to become aware of a remarkable set of nine maps, all uncolored, which furnish a unique tool of clear potential value that has never been realized because of persistent neglect. These nine comprise a modern representation of the Roman world from the Antonine Wall in Scotland to Hierasycaminos on the border between Egypt and Nubia2 at a uniform scale of approximately 1:3,400,000, on which are traced out in detail the ‘routes’ appearing on the Peutinger Map and listed in the Antonine Itinerary (ItAnt) and Bordeaux/Jerusalem Itinerary (ItBurd). Even mutationes (the least notable stopping-points) recorded by ItBurd are marked ! This set of maps was produced as part of a two-volume project commissioned by the extraordinary aristocrat Agricol Fortia d’ Urban (1756-1843),3 but only published posthumously in 1845 at his heir’s expense by the Imprimerie Royale, Paris: Recueil des Itinéraires Anciens comprenant l’ Itinéraire d’ Antonin, la Table de Peutinger et un choix des périples grecs, avec dix cartes dressées par M. le Colonel Lapie. A quarto ‘text’ volume comprises lists (in four columns) of the ‘routes’ in each of these sources in turn, place by place, appending the modern equivalent name where possible, and stating the distance figure for each stretch as it appears in Roman numerals in the source, together with the arabic-numeral equivalent, as well as the actual distance on the ground in Roman miles (arabic figures) as calculated by Lapie (Fig. 1 at the end reproduces a sample page).4 The Peutinger Map section (pp. 197- 320) takes Rome as its starting-point, and comprises 235 numbered routes; it is followed, moreover, by an alphabetical listing of those names to be found on the Map which are detached from its route network. The Préface to the text volume – signed by Emmanuel Miller (1812-1886) – states (p. I) that Lapie’s maps “....devaient être mises en rapport avec le texte, et représenter toutes les positions, toutes les localités, toutes les dénominations géographiques contenues dans l’ Itinéraire d’Antonin, dans la Table de Peutinger et dans les Périples grecs.” Miller elaborates further (p. XVIII): “L’atlas joint à cette édition se compose de neuf feuilles, qui peuvent être réunies en une seule, représantant tout l’empire romain, avec l’indication de toutes les dénominations géographiques comprises dans cette collection des itinéraires. Une dixième feuille est 1 = Zichoi, Map 84E4 in R.J.A. Talbert (ed.), Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World (Princeton and Oxford, 2000). 2 BAtlas 9C5 to 81C2. 3 M. Michaud (ed.), Biographie Universelle vol. 14 (Paris, 1856), 429-32. 4 The text volume of Lapie’s: Recueil des Itinéraires Anciens comprenant l’ Itinéraire d’ Antonin, la Table de Peutinger et un choix des périples grecs, avec dix cartes dressées par M. le Colonel Lapie, Paris 1845 could now read online and downloaded from the French National library at http://gallica.bnf. fr/ (HMS ed.). 150 spécialement destinée à Marcien d’Heraclée et à Isidore de Charax; elle a déjà paru à la suite de mon Supplément des Petits Géographes.”5 Because of their larger size, Lapie’s maps were issued in their own folio volume, and the nine do indeed form a 3 x 3 set (numbered 1-9 in horizontal sequence) that can readily be assembled to form one piece (cf. maps 1-10 at the end of the book).6 Each map is a bi-folio sheet with a single vertical fold, printed on one side only, with no overlap of coverage, and with a conspicuous border drawn to mark the edges of the set. Map coverage is as much as 51.5 cm wide x 37.5 on a sheet. Assembled, the nine sheets span approximately 150 cm wide by 109, within which some space is reserved for insets, explanatory data, etc. The prime meridian for the graticule runs through Paris. Rendering of elevation is limited, but mountain ranges are shown by hachuring. Only ancient names are marked, very legibly engraved however tiny they may be.7 It is striking that an attempt is made – in accordance with the listing mentioned above – to mark even names and notices on the Peutinger Map that are detached from its route network. Top left on sheet 1 appears the heading: ORBIS ROMANUS AD ILLUSTRANDA ITINERARIA ANTONINI BURDIGALENSE TABULAM PEUTINGERIANAM PERIPLOS ITINERARIA MARITIMA DELINEATUS A P. LAPIE GEOGRAPHO IN COMITATU REGIO MILITARI CHILIARCHA IN ADMINISTRAT RER BELLIC COLL TOPOGRAPH PRAEFECTO LUTETIAE A M DCCC XXXIIII, and, in tiny letters underneath, “Flahaut sculpt.”8 At the top of sheet 3, scalebars for the main map are presented in as many as eight different units: Miliaria Romana; Leucae Gallicae; Stadia quorum 700 intra unius Gradus spatium continentur; Stadia Olympica; Parasangae Persicae; Schoeni Aegyptiaci; Milliaria (sic) Judaica. No scale figure is stated for the map (nor for any of the insets), but it is in fact approximately 1:3,400,000. The top right corner of sheet 3 is occupied by a large inset “URBS cum adjacentibus regionibus” with a scalebar in Roman miles and no graticule; this inset’s scale is approximately 1:1,000,000. Immediately below is a tiny inset, without title or scalebar, that covers Atella-Cumae-Aenaria ins.-Neapolis; its scale is approximately 1:800,000. On sheet 6 the width of the main map is slightly reduced to accommodate a ‘bleed’ towards the bottom right, 2.6 cm in width, which extends the coverage to Ctesiphon and Babylon, as well as to Vologesia. Sheet 7 only continues coverage of the main map at its very top (as far south as Autolole in Africa). Otherwise it accommodates a substantial 5 The tenth (unnumbered) map is the same size as the other nine, but otherwise a quite separate and elaborate item entitled “TABULA exhibens loca a MARCIANO HERACLEOTA ISIDOROque CHARACENO memorata,” with six insets. As Miller indicates, it is a revision of the map which he had already published to accompany his edition (Paris, 1839) of the Greek geographical writers named and others; see further the Introduction générale to D. Marcotte, Géographes Grecs I, Paris, 2000 (Budé series), CLX and n. 310. 6 Multiple thanks to Harvard University: David A. Cobb (Harvard Map Collection) arranged for the set of maps held by Andover Theological Library (Divinity School) to be scanned by the Digital Imaging Graphics Department (Widener Library). This set has suffered some foxing. I am grateful to Jeffrey A. Becker (Ancient World Mapping Center, UNC, Chapel Hill) for assembling it and supervising a trial printout; inevitably, a perfect fit cannot be achieved at every point. 7 On the continuing preference for engraved maps, with all their associated labor and expense, long after lithography had become demonstrably cheaper and more efficient during the first quarter of the nineteenth century, see R.J.A. Talbert, “Carl Müller (1813-1894), S. Jacobs, and the making of classical maps in Paris for John Murray,” Imago Mundi 46 (1994) 128-50, esp. 144. 8 In J. French (1-2) and V. Scott (3-4) (eds.), Tooley’s Dictionary of Mapmakers, 4 vols, revised ed. (Riverside, CT, 1999-2004), the entries s.v. Flahaut reveal that two individuals divulging no more than this single name engraved many of Lapie’s maps between the 1820s and 1840s; at least one (“Mlle”) was female. 151 reduced-scale map9 (with graticule) which ranges from Amastris to the mouths of the Ganges; the scale is approximately 1:11,000,000. At bottom right on sheet 8 there appears the key to the eight styles in which route linework is drawn throughout: Itinerarium Antonini; Burdigalense; Tabula Peutingeriana Itin Ant; Tab. Peuting. Itin. Antonini Tabula Peutingeriana Itin Burdigal et Anton Itin Burdigalense Itin Burdigal; Tab Peuting Viae Romanae, de quibus silent scriptores veteres.10 Inevitably, the eight variants are not all easy to differentiate, because the linework is thin and its presentation in color impractical (even so, purchasers could add color themselves). A further challenge to the user is the fact that in some regions – Italy and Crete, to name but two – the quantity of data to be accommodated pushes both the chosen scale and the engraver’s skill to their limits. In addition naturally, as with any map, there is scope for disagreement about rendering of landscape, placement of names and routes, and so forth.11 As always, too, new findings created constant pressure for revision. Indeed the Préface explains that revision was undertaken for North Africa and Asia Minor even before the maps were issued (meantime sheet 1 at least, dated 1834, had already been produced). Such concern to keep up-to-date only underlines the favorable reputation enjoyed by the experienced cartographer, Col. Pierre Lapie (1777-1850),12 not to mention that of the classical scholars led by Emmanuel Miller who supplied the ancient data. In retrospect, we may consider them all unduly modest about the ambitious and pathbreaking character of their collaborative achievement. The standard edition of the itineraries in the 1830s, by Peter Wesseling,13 was a century old, and it neither referred to maps nor provided any. As to the Peutinger Map, only one complete commentary had achieved publication, by Mathias Peter Katancsich (1750-1825).14 He, too, creates routes (but omits to number them) comparable to the 235 organized by Miller. He also attempts to determine the modern equivalent name and location of places marked by the Map, demonstrating cartographic awareness for the purpose. But he provides no maps beyond an engraving of the Peutinger Map itself, and he reflects eighteenth-century knowledge at best, 9 TABULA ASIAE INTERIORIS AD EXPLANATIONEM TABULAE PEUTINGERIANAE MARCIANI HERACLEOTAE ISIDORI CHARACENI. Scalebars for only three units are offered here: Milliaria (sic) Romana; Stadia; Parasangae Persicae. 10 Despite the potential for confusion, no reference is made to the fact that this style of linework is also used to trace the crossings of open water that occur in ItAnt and ItBurd, together with some others. How and why only these latter crossings were chosen for inclusion eludes me. In particular, the Itinerarium Maritimum is not followed systematically. To be sure, inclusion of its coastal routes would often create acute difficulties of presentation where there is already no practical alternative to placing the names of many coastal settlements in open water. 11 Tony would be the first to query the naming of the Antonine Wall as Vallum Severi ! 12 M. Michaud (ed.), Biographie Universelle vol. 23 (Paris, n.d.), 228-29 (by A. Maury). Lapie, it should be appreciated, was no classical scholar, and made historical maps strictly on the basis of data supplied to him: see W. Goffart, Historical Atlases: the First Three Hundred Years, 1570-1870 (Chicago, 2003), 15, 386. 13 Vetera Romanorum Itineraria, sive Antonini Augusti Itinerarium, Itinerarium Hierosolymitanum, et Hieroclis Grammatici Synecdemus (Amsterdam, 1735). 14 Orbis Antiquus ex Tabula Itineraria quae Theodosii Imp et Peutingeri Audit ad systema geographiae redactus et commentario illustratus (2 vols, Buda, 1824-25). 152 because his work, although completed by 1803, was not published for a further twenty years. Hence Lapie’s production of a large, modern representation of the Roman world on which the Peutinger Map’s routes, as well as those of the Antonine Itinerary and Bordeaux Itinerary, are all traced in detail and integrated is an extraordinary advance. None of this data had been mapped out thus before, nor has a map been produced since which features it all. ********** Reference is duly made to Lapie’s map volume by Carl Müller – for many years a Paris resident – in his Geographi Graeci Minores especially.15 Further use of it by him would no doubt have been evident too, had he ever brought to publication the projected third volume of this work, or his edition of the Peutinger Map which supposedly was close to completion by the early 1870s.16 As it is, studies of the Peutinger Map as well as of the Antonine and Bordeaux Itineraries have all but ignored Lapie’s unique contribution. The edition of the itineraries published by Gustav Parthey and Moritz Pinder in 184817 to replace those of Wesseling and Miller does refer in its Index to modern equivalent names for ancient places proposed by Lapie, and it also offers its own lithographed map drawn by Parthey with a single inset (“Viae ex Urbe exeuntes” at 1:840,000). The 1:11,000,000 scale for the main map, however, is so small that the less notable stopping-points cannot be shown. The few stretches of route traversed only in ItBurd are identified as such, but not the routes covered by both ItBurd and ItAnt, nor most routes which require an open-water crossing. Printing in one color is a welcome enhancement, but it might have proved more useful to employ this blue to highlight route linework rather than shorelines and the course of the Tiber. At the end of his long Realencyclopädie entry ‘Itinerarien’ published in 1916,18 Wilhelm Kubitschek mentions Parthey’s map and those of Lapie only to dismiss all of them brusquely as unusable: “Die Route von ItBurd hat Parthey in seine Übersichtskarte zum ItAnt mit hineingezeichnet, aber in so unglücklicher Technik, dass sie unverwendbar bleiben musste. Die Karte von Lapie ist aus demselben Grunde, eben durch dieselbe Art von Verquickung mit dem ItAnt unbrauchbar.” More damaging for the long term has been the absence of any mention of Lapie’s maps in the 1929 Teubner edition of the itineraries by Otto Cuntz, which remains standard.19 The map accompanying this edition, drawn by Cuntz himself, is at a somewhat larger scale (1:10,000,000) than Parthey’s and adds some open-water routes, but otherwise amounts to no more than an inferior version of his. Cuntz does not employ color, dispenses with Parthey’s inset altogether, and omits most rivers along with the many names of peoples and regions. Predictably enough, even the most intensive recent analyses of the itineraries make no reference at all to Lapie.20 Nor does Bernd Löhberg, the first scholar since Lapie to map the 15 2 vols, Paris, 1855 and 1861; see further Talbert, op. cit. in n. 6 above. 16 So he claims himself with reference to Map 29 Asia Minor in the ‘Sources and Authorities for the Maps’ section of W. Smith and G. Grove (eds.), Atlas of Ancient Geography Biblical and Classical .... (London, 1872-1874). 17 Itinerarium Antonini Augusti et Hierosolymitanum (Berlin). 18 RE 9. 2308-63 at 2363. Attention is still drawn to Lapie’s set of maps, however, in F. Cabrol and H. Leclercq (eds.), Dictionnaire d’archéologie chrétienne et de liturgie VII (Paris, 1927), s.v. Itinéraires, col. 1861 [by Leclercq]. 19 Itineraria Romana I: Itineraria Antonini Augusti et Burdigalense (Leipzig). Cuntz’s text of ItBurd (only) is revised by P. Geyer, 1-26 in Itineraria et Alia Geographica (CCSL 175), Turnholt, 1965. 20 Especially M. Calzolari, Introduzione allo Studio della Rete Stradale dell’ Italia Romana: L’ Itinerarium Antonini, Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei (Classe di Scienze Morali, Storiche e Filologiche) Memorie Ser. IX vol. VII fasc. 4 (1996) 369-520; and id, “Ricerche sugli itinerari romani. L’ Itinerarium Burdigalense,” in Studi in Onore di Nereo Alfieri, 127-89 (Accademia delle Scienze di Ferrara, 1997). In addition, for a variety of perspectives 153 routes of the Antonine Itinerary (only) on a modern representation of the Roman empire.21 Löhberg takes maps from the Barrington Atlas (2000) as his base, reproduces them in full color, and highlights the relevant routes most conspicuously in red.22 The result – published in 2006 – underscores his creative ability to harness recent developments in digital technology. Even so, users might wish that he would dare to advance further by issuing an electronic version too, where the individual printed pages of maps were mosaiced together, and at one scale. Meantime, constant recourse to the Strassen- und Blattübersicht23 is required in order to follow longer routes through 152 maps from the Barrington Atlas presented on 140 pages, with many insets, and frequent shifts of scale between 1:500,000 and 1:1,000,000. No map extends beyond a single page, with approximately 16.5 cm wide x 25.2 the maximum frame. ********** In the case of the Peutinger Map, Ernest Desjardins attempted to replace Katancsich’s commentary from 1869, but only brought his coverage of Gaul and Italy to publication in fourteen fascicles,24 the last two of them issued in 1874. Desjardins places no reliance upon Lapie, but partially supersedes his work by providing three impressive modern color maps of his own in the last two fascicles, on which the routes in Gaul and Italy are traced.25 To date, the only other editor of the Peutinger Map has been Conrad Miller, whose coverage in the single volume Itineraria Romana (Stuttgart, 1916) is complete. Like Desjardins, Miller offers his own modern base maps, indeed more than 300 of them, but they are the most minimal uncolored sketches at varying scales (often unstated), dispersed through his volume.26 Modern toponyms are written in a cursive script very resistant to decipherment by today’s reader. Above all, there is no comprehensive presentation at a uniform scale, nor even a reference to Lapie’s maps except for a single bibliographic listing in small print (p. LIII). The only other reference that Miller makes to the work sponsored by Fortia is limited to the correction of some misunderstanding that its scope included a revised presentation of the Peutinger Map itself (p. XXV). Miller was undoubtedly aware of Lapie’s maps, therefore, and of the fact that they provided a valuable conspectus of the Peutinger Map’s scope and detail from a modern viewpoint. But Miller chose not to draw attention to this contribution, even though his own edition failed to offer the equivalent. This choice on his part – guileless though it may have been – has had an unfortunate effect in the long term. For almost a century now, Miller’s edition of the Peutinger Map has generally been assumed to encapsulate and supersede all previous scholarship. Earlier work has more and more been ignored in consequence, including Lapie’s remarkable set of maps. without mention of Lapie, compare B. Salway, “The perception and description of space in Roman itineraries,” 181- 209 in M. Rathmann (ed.), Wahrnehmung und Erfassung geographischer Räume in der Antike (Mainz, 2007), with R.J.A. Talbert, “Author, audience and the Roman empire in the Antonine Itinerary,” 264-79 in R. Haensch and J. Heinrichs (eds.), Herrschen und Verwalten: Der Alltag der römischen Administration in der Hohen Kaiserzeit (Berlin, 2007). 21 Das ‘Itinerarium provinciarum Antonini Augusti,’ ein kaiserzeitliches Strassenverzeichnis des Römischen Reiches: Überlieferung, Strecken, Kommentare, Karten (2 vols, Berlin, 2006). 22 However, the opportunity to show where ItAnt routes duplicate one another is not taken. 23 A loose endpaper at 1:15,000,000. A duplicate showing only Die Strassen is provided too. 24 La Table de Peutinger, d’ après l’ original conservé à Vienne ..... (Paris). 25 For details, see R. Talbert, “Cartography and taste in Peutinger’s Roman map,” 113-41 in id. and K. Brodersen (eds.), Space in the Roman World: its Perception and Presentation (Münster, 2004) at 133. 26 A set of twelve such sketches is more conveniently brought together, however, in Miller’s revised Die Peutingersche Tafel (Stuttgart, 1916). This work offers a brief overview of Itineraria Romana together with a pullout half-size lithograph of the Peutinger Map; for details, see Talbert, op. cit. in previous note, 134-35. 154 The way forward today, as Löhberg has demonstrated, lies with the computer and digital technology. These now provide the means to create a modern representation of the Roman world at a uniform scale, and to mark on it in layers all the route stretches recorded by the Peutinger Map, Antonine Itinerary and Bordeaux Itinerary. The scale can be instantly adjusted up or down. The layers can be integrated, manipulated and superimposed on one another with a clarity and readiness that Lapie strove for, but could not attain. This is the versatile tool that is currently being prepared in connection with my own forthcoming presentation of the Peutinger Map. Richard Talbert University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill At the same time as arguing here that the study of Roman history would have benefited from engagement with Lapie’s map of the empire, I cannot help reflecting on the loss that Roman history in North America suffered when Tony returned to Europe after only a short period of teaching at Duke University – close neighbor to UNC, Chapel Hill – during the 1960s. I was an admirer of Tony’s work long before I ever met him. It was at Duke of all places that I first did so, when he returned on a visit to lecture there thirty years or so later. What a privilege and stimulus it would have proved to have him as a colleague nearby! Fun too.

155

M. Calzolari, Introduzione allo Studio della Rete Stradale dell’ Italia Romana: L’ Itinerarium Antonini, Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei (Classe di Scienze Morali, Storiche e Filologiche) Memorie Ser. IX vol. VII fasc. 4 (1996) 369-520 id, “Ricerche sugli itinerari romani. L’ Itinerarium Burdigalense,” in Studi in Onore di Nereo Alfieri, 127-89 (Accademia delle Scienze di Ferrara, 1997)

O. Cuntz, Itineraria Romana I: Itineraria Antonini Augusti et Burdigalense, Leipzig, 1929 (Teubner)

E. Desjardins, La Table de Peutinger, d’ après l’ original conservé à Vienne (14 livraisons, Paris, 1869-74)

A. Fortia d’ Urban, Recueil des Itinéraires Anciens comprenant l’ Itinéraire d’ Antonin, la Table de Peutinger et un choix des périples grecs, avec dix cartes dressées par M. le Colonel Lapie (2 vols, Paris, 1845)

J. French (1-2) and V. Scott (3-4) (eds.), Tooley’s Dictionary of Mapmakers, 4 vols, revised ed. (Riverside, CT, 1999-2004)

P. Geyer, Itinerarium Burdigalense in Itineraria et Alia Geographica, Turnholt, 1965 (Corpus Christianorum Series Latina 175), 1-26

W. Goffart, Historical Atlases: the First Three Hundred Years, 1570-1870 (Chicago, 2003)

M. P. Katancsich, Orbis Antiquus ex Tabula Itineraria quae Theodosii Imp et Peutingeri Audit ad systema geographiae redactus et commentario illustratus (2 vols, Buda, 1824-25) B. Löhberg, Das ‘Itinerarium provinciarum Antonini Augusti,’ ein kaiserzeitliches Strassenverzeichnis des Römischen Reiches: Überlieferung, Strecken, Kommentare, Karten (2 vols, Berlin, 2006)

D. Marcotte, Géographes Grecs I, Paris, 2000 (Budé)

C. Miller, Itineraria Romana (Stuttgart, 1916) id, Die Peutingersche Tafel, revised ed. (Stuttgart, 1916)

C. Müller, Geographi Graeci Minores (2 vols, Paris, 1855, 1861)

G. Parthey and M. Pinder, Itinerarium Antonini Augusti et Hierosolymitanum (Berlin, 1848)

B. Salway, “The perception and description of space in Roman itineraries,” 181-209 in M. Rathmann (ed.), Wahrnehmung und Erfassung geographischer Räume in der Antike (Mainz, 2007)

W. Smith and G. Grove (eds.), Atlas of Ancient Geography Biblical and Classical (London, 1872-1874)

R. J .A. Talbert, “Carl Müller (1813-1894), S. Jacobs, and the making of classical maps in Paris for John Murray,” Imago Mundi 46 (1994) 128-50 id. (ed.), Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World (Princeton and Oxford, 2000) id, “Cartography and taste in Peutinger’s Roman map,” 113-41 in id. and K. Brodersen (eds.), Space in the Roman World: its Perception and Presentation (Münster, 2004) id, “Author, audience and the Roman empire in the Antonine Itinerary,” 264-79 in R. Haensch and J. Heinrichs (eds.), Herrschen und Verwalten: Der Alltag der römischen Administration in der Hohen Kaiserzeit (Berlin, 2007)

P. Wesseling, Vetera Romanorum Itineraria, sive Antonini Augusti Itinerarium, Itinerarium Hierosolymitanum, et Hieroclis Grammatici Synecdemus (Amsterdam, 1735) 156

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |