|

ABRAHAM ORTELIUS (1527-1598)

|

|

Cartographica Neerlandica Map Text for Ortelius Map No. 227

Text, translated from the 1624 Latin edition of the Parergon; this text is contained in the 1641 Spanish edition as well. The introduction to these maps occurs at the end of the preceding map, Ort226, Argonautica: Ort226.112 = Ort227.0.

{1624LParergon/1641S only{BALTHASAR MORETVS LECTORIS:

TABVLAM ITINERARIAM antiquam ordine suo hîc insero, octo distictam segmentis, & quattor folijs comprehensam. quam ORTELIVS, curã & ære suo iam pæne absolutam, patri meo: IOANNI MORETO, veteris amoris sui testimonium, moriens legauit: eã lege, vt perfici curaret; & Nobilißimo ac Doctissimo Viro MARCO VELSERO remitteret ; cuius nempe beneficio,in illustri PEVTINGERORVM Bibliotecã repertam, acceperat. Que TABVLAM illustret , ipsius VELSERI ad eius Fragmenta (quæ pleniori Libello explicauit) Præfationem meritò appono; qua de Tabulæ Auctore , ætate , usu , alijsque , eruditè atque utiliter disseruit. & quod de eadem , postquam integram nactus esset, alieno licet nomine , iudicium tulit, coronidis vicem adiungo. Vale, beneuole Lector, & præclaro Antiquitatis monumento fruere}1624LParergon/1641S}. [Balthasar Moretus to the reader: The TABVLA ITINERARIA or travel map. I here insert an ancient map in its proper order, ornated in eight distinct sections, and depicted on four sheets, which ORTELIUS with diligence, and at his own expense had almost finished, and which he, dying, dedicated to my father under the condition that he would take care of its completion, as a token of his lasting devotion, and would return it to the very honourable and learned Marcus VELSERUS, through whose generosity he discovered it in the famous PEUTINGER library, where he obtained it. Which map he would make accessible. And the remarks of VELSERUS (described by him in an exhaustive booklet) are added here with a preface, saying which author, time, application and other aspects of the map have been discussed by him learnedly and usefully, and what opinion he held about it himself, after he had received it undamaged, is added here as a counterachievement for its final shape. Farewell, Reader, and enjoy this splendid memorial of antiquity].

227.1. {1624L{Ancient Road Map

[column 1]

227.2. Preface to the map fragments by Marcus Velserus:

In which its designer, its age, its use and some other explanatory and clarificatory matters are discussed.

227.3. B[eatus] Rhenanus in his books on Germany refers various times to a map which he saw at the house of his friend Chunradus Peutingerus in Augst. At various places he calls it a regional map, a road map, or a military map.

227.4. He estimates that this map must have been designed in the time of the last Roman emperors, and that it has been retrieved by Celtis [Cunradis Celtis Peutingerus, born in Pickel, 1459-1508, readily associated with the Peutinger map] in some library or other. Its ancient nature is supposed to be beyond any doubt.

227.5. When he adduced some proofs for this view, he aroused an intense desire in many people to inspect it. Learned scholars considered this map to be a decisive factor for establishing irrefutable borders; many long-standing, unsolvable disputes among scholars of history might be settled for once and for all by this map.

227.6. It is true that Peutingerus failed to publish this map during his life time, so much is evident to me, and it has not been studied further by anyone in spite of many insistent requests. However, among the literary treasures which he left behind after his death, two sheets have been found which seem to have been drawn up on the basis of that map. One shows a larger area than the other, but none of the two shows the entire original, as becomes clear from some specific details.

227.7. When these sheets [first (right) page, column 2] came into my hands, I considered them to be worthy of publication, so as not to be envied by the public. I have therefore published them diligently to such an extent that to some this would almost seem to be exaggerated; I have devoted attention to its broad outlines as well as to its details, and I preferred to amend evident mistakes in my comments on it, rather than on the map sheets themselves. But no one is sufficiently accurate when rendering ancient monuments when in fear of thus making predictions.

227.8. It is not because of its publication that I entrust this task to many: either the manuscript has been lost, or it lies in hiding in such an unlikely place that it will not be retrieved; (if this were a prediction, it would truly be a commendable one), but anyway, I am certain that all scholars will show their gratitude when meanwhile they can enjoy the study of these fragments.

227.9. I consider it mandatory to add some comments to it. It is not my intention to act like an oracle whenever investigations cannot provide concrete evidence; many place names are now for the first time disseminated, and those which were uncorrupted are passed on by me now, but I was unable, in spite of great mental efforts, to establish which place names either in their complete form, or as parts, reminded me of something or other, and it seems to me that all the same the readers will be edified by this work.

227.10. And I ran the risk that if I would publish these sheets in a rather bare form, many who knew about their existence would dismiss them, without considering them to be worthy of a second look, and I have not avoided to perform the exacting task of correcting the mistakes of the copyists, to explain matters in a clear way which by the maker were presented obscurely, to establish with certainty what at first sight was uncertain and of dubious significance, and finally to note down when certain matters seemed to be mistakes by the author of the map.

227.11. For either I am mistaken, or it is precisely these bumps on the road to truth which prevented Peutingerus, who fostered study of the ancients with more devotion than anyone, to publish it.

227.12. I will therefore warn few people for what turns out to be considerable, without any bragging or contempt.

[next page first map sheet, column 1]

227.13. For why would I either please myself if I do not stray from such a course, or why would I simplify the devotion of others when they have strayed in such dense clouds from the past? Whatever the case might be, it would not lead them to err, nor add to my own glory. Not that I am intent on doing so, but I am convinced that my efforts only bear fruit if I, with these comments, can illuminate the road traversed by those who study these map sheets.

227.14. I will first give my verdict concerning the maker, the map, the map sheets, the roads and their numbers. I will then come to speak about individual place names.

The maker of this map was not well-versed in geography, nor was he well educated in mathematics, we have to concede that; this is self-evident, for neither the shapes of provinces and their form, nor the coast lines, nor the course of rivers, nor the distances between various places match those of the models of the [established] geographers. I hope that there will not be great distrust when among such a large amount of place names there may sometimes be one introduced by measurements of some surveyor or other which is not founded on solid science.

227.15. For land surveyors, according to Vegetius in his second book, chapter 7, are those who choose the site for the next encampment. For him [i.e. Vegetius] it is therefore the surveyors who decide about distances on behalf of the military. But it must have been the case that those who in civil circles decided on inns and guest houses [to be used for the military] were called land surveyors. In this respect I refer to the Codex of Books, Book 2, title 8 line, 3 and 5, Book 12 title 19. line 9, title 41. line 1, 2, 5, 9 and 11.

227.16. The required knowledge about routes, crossings, places, distances and numerous other matters related to the acquisition of knowledge about these matters, was clearly to be obtained from land surveyors. For I have no doubts that when deciding on routes to be followed, land surveyors were consulted by military leaders. By way of example, note what Lampridius [one of the supposed authors of the Historia Augusta, describing emperors' lives in the third century A.D.] says on the authority of Alexandrus Severus:

227.17. The route will be announced on a certain day in such a manner that two months in advance the itinerary is made public in the following manner: at that day and hour, I must leave the city and, with the help of the gods, I will pass the night in the first night quarter. Then there follows an edict list of night quarters, the encampments and the places where rations will be distributed. These itineraries can only have been drawn up by an experienced land surveyor who was well acquainted with the night quarters, their respective distances, their size and the amount of ration, on the basis of which he could prescribe which part of a military unit could appropriately be accommodated in one of the night quarters. I am also fully convinced that the Province Itinerary ascribed to Antoninus Augustus, which we are used to rely on as an authoritative work, is fully based on the knowledge of land surveyors.

227.18. For whatever Lampridius calls an edict is by D. Ambrosius in sermon 5 concerning Psalm 118 called an Itinerary. It is appropriate to quote here in full the [relevant] passage, since it illustrates our purpose: A soldier starting on a journey does not decide on his own which route to follow, nor does he take a road after his own view, nor does he take shortcuts as he likes, and he does not stray from his banner, but he receives his Itinerary from the emperor, and he sticks to it. He advances in the prescribed order, and marches carrying his weapons; he continues his journey along the road prescribed, so that he will receive support. If he would choose to follow a different route, he would not receive rations, and would not find night quarters prepared for him.

227.19. Because of the emperor's order that everything must be prepared for those following him, those had better adhere to the route prescribed. And whoever follows the emperor will receive ample reward; he will march at a reasonable pace, because the emperor will not travel at a pace which pleases him, but decides to choose a pace which everyone can follow. This is why he has ordered fixed encampments; a military unit marches for three days and will rest on the fourth day. Cities will be chosen that lie at a distance of three, four or more days of marching, provided they have sufficient water and merchant traffic. Thus the soldier's journey will be accomplished without difficulties}1624LParergon/1641S}

(Here ends the text of the first mapsheet, which will be continued on Ort228).

|

Cartographica Neerlandica Background for Ortelius Map No. 227

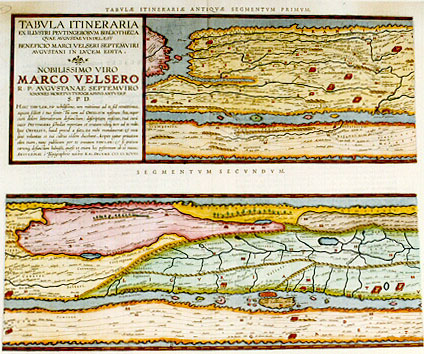

Title: TABVLA ITINERARIA | EX ILLVSTRI PEVTINGERORVM BIBLIOTHECA | QVAE AVGVSTAE VINDEL. EST | BENEFICIO MARCI VELSERI SEPTEMVIRI | AVGVSTANI IN LVCEM EDITA. | NOBILISSIMO VIRO | MARCO VELSERO | R.P. AVGVSTANAE SEPTEMVIRO | IOANNES MORETVS TYPOGRAPHVS ANTVERP. | S.P.D. | "HANC TABVLAM, Vir nobilißime, non mittimus ad te, sed remittimus, | aquam scilicet è tuo fonte. Tu eam ad ORTELIVM nostrum (heu, nupe r| cum dolore litteratorum defunctum) descriptam miseras, tuâ curâ | inter PEVTINGERI schedas repertam et erutam: ideoque iure ad te redit. | Ipse ORTELIVS, haud procul a fato, ita mihi mandaverat: & mea | sane voluntas et tui cultus eôdem ducebant. Accipies igitur priuatam | olim tuam, nunc publicam per te omnium TABVLAM: & si gratum | carumque defunctum habuisti, quæso vt etiam hoc postremum ab eo munus. | ANTVERPIÆ è Typographeio nostro". KAL. DECEMB. M.D.XCVIII. [Road map from the famous library of the family Peutinger from Augsburg in Bavaria, brought to light by Marcus Welser from Augsburg, belonging to the council of seven. Joannes Moretus, publisher in Antwerp, dedicates this map to the very noble gentleman Marcus Welser. This map, very noble lord, is not being sent to you by us, but is returned, water as it is from your fountain. You have sent its design to our Ortelius (who alas, to the misery of all literary people, is now deceased), after it had been located and found back by your diligence between the manuscripts of Peutinger, and therefore it is rightfully returned to you. Ortelius himself has ordered me to do so, shortly before he died; and both my own desire as well as my respect for you prompted me towards this goal. You will therefore receive this map, once your private property, now through you public property of everyone. And as much as the deceased was dear to you, I hope that this last present from him will be equally dear to you. Antwerp, by our typographer (Plantin-Moretus) First of December 1598.] (This is the first sheet of the set of four, and contains segments one and two).

Plate size (2 plates): (top:) 193 x 516 mm, (first state only:) A engraved at midbottom; (bottom:) 193 x 516 mm. Two (potentially adjacent) maps on two plates.

Scale: not applicable.

Identification number: Ort 227 (Koeman/Meurer: 44P, not in Karrow, van der Krogt AN: 0910:1:31).

Occurrence in Theatrum editions and page number:

1619BertiusII, (200 copies printed) (last line first text page, centred: PRIMVM ET SECVNDVM. (see further below),

1624P/1641Sxliij (1025 copies printed) (last line first text page, in two columns; first column: diciis liquet. Hæc cùm ad manumeas Second column: que non pauca paucis, sine ostenta-|tione).

Approximate number of copies printed in the Theatrum: 1225.

States: 227.1 only. However, the text has three states:

-The first text state occurs in a few separately printed Peutinger maps of 1598. These sheets have no text on verso and no texts above the 8 map strips on the four map sheets Ort227-Ort230.

-The second text state occurs in Bertius' 1618/1619 atlas Theatri Geographiae Veteris Tomus Posterior, page II, 1619, text in two columns, last line first text page, second column, left aligned: "cessoribus nostris relinquamus". Text above first map strip: TABULÆ PEVTINGERIANÆ SEGMENTVM PRIMVM, "ab ostiis Rheni Bonnam vsque". Text above second map strip: SEGMENTVM SECVNDVM "à Bonna ad Marcomannos".

-The third text state occurs in the 1624Latin Parergon/1641 Spanish edition, but text in Latin, last line first text page, second column, right aligned: tione, ; text above first map strip: TABVLÆ ITINERARIÆ ANTIQVÆ SEGMENTVM PRIMVM. text above second map strip: SEGMENTVM SECVNDVM.

Cartographic sources: as early as 1578, Ortelius knew about the existence of a series of manuscript road maps, showing the Roman view of the world at around the third century. The original, found by Konrad Celtes (1459-1508) in a library in Augsburg, came into the hands of Konrad Peutinger (1465-1547) and later went to his relative Mark Welser. Welser was the first to publish a copy of it in 1591 at Aldus Manutius in Venice. Ortelius found this copy inadequate. Therefore, in 1598 new manuscript copies were made at his request by Welser. The present set of eight (adjacent) maps on four sheets were engraved following these copies. The original Peutinger maps disappeared, were retrieved in 1714, and are now in the Vienna National Library. Because of damage and progressive blackening of the 11 (once 12) sheets of parchment, Ortelius' version is now the most reliable representation. Ortelius supervised the engraving, but did not live to see the result, which was first published separately in 1598 by Moretus. Bertius included these prints in his "Theatrum Geographiæ Veteris" without text except for the first map sheet, but with geographical indication per strip, in 1619. The text used is an abstract of the text which appeared in the 1624 Parergon (probably already written in 1598 by Ortelius), mostly including the text of the last sheet, Ort230. Only in 1624 did these maps finally appear in the last edition of Ortelius' Parergon, produced by Plantin-Moretus.

References: H. Gross (1913) "Zur Entstehungs-geschichte der Tabula Peutingeriana", Reprint, Meridian Amsterdam, 1980; E. Weber (1976) "Tabula Peutingeriana", Codex Vindobonensis 324, (facsimile), Graz; P. Stuart (1991/1993) "De Tabula Peutingeriana" I, II, Museumstukken, Museum de Kam, Nijmegen; O.A.W. Dilke (1987) in Harley-Woodward's History of Cartography Vol. I. p. 238 ff., University of Chicago Press; P.H. Meurer "Ortelius as the Father of Historical Cartography", p. 133-159 in: M. van den Broecke, P. van der Krogt and P.H. Meurer (eds) "Abraham Ortelius and the First Atlas", HES Publishers, 1998.

Remarks: selection of cities in the first segment (from left to right, place names as now used in that location): Bordeaux, Exeter, Dover, Richborough, Toulouse, Kassel, Rennes, Loire, Rouen, Doornik, Amiens, Narbonne, Soissons, Nijmegen, Nîmes, Reims, Xanten, Tongeren, Arles, Lyon. In the second segment a.o.: Metz, Trier, Koblenz, Fréjus, Lac Léman, Mainz, Worms, Speyer, Strassbourg, Torino, Genoa, Corsica, Sardinia, Pisa, Augsburg, Milano, Bergamo, Piacenza, Firenze. |

|

|

Cartographica Neerlandica Map Text for Ortelius Map No. 228

Text translated from the 1624L edition, which also occurs in the 1641 Spanish edition:

(First column, the text is a continuation of that of Ort 227:)

228.1. {1624L/1641s{until he arrives in a city chosen as it were by a king, in which the tired military unit will rest. I would like to convince you that this ruling has been prescribed under the guidance of Christ and with the help of the Holy Saints. This has been achieved, and our fathers have come from the land of Egypt, over a vast stretch of land, of which all military camps and quarters have been described, come to Cades, that is, the Holy Land.

228.2. Thus you see the use of an Itinerary, and this is also what other authors have concluded. Truly, in this context the [following] poet is very credible [cited from Horatius'Ars Poetica, line 180-182]:

228.3. Less is engraved in the mind what is perceived by ear

Than what is entrusted to the trustworthy eyes

And what the viewer entrusts to himself...since Itineraries are illustrated with drawn maps. In this manner, no doubt, the emperor could see in one glance the orientation of roads and night quarters on a map. All this was very much a result of the fact that these matters belonged to the duties of the emperors. If a part of the army had to be moved from Lugdunum Batavorum [Leiden] to Noviomagus [Nijmegen], it would be helpful to visualise this task: either because of the size [of a marching army], or for other reasons, there are two ways to go from one to the other: the right one, along the right bank of the river [Rhine] is subdivided into six night quarters; and the left one, along the left bank, was subdivided into nine night quarters.

228.4. The area beyond the river valley was enemy territory, the other [valley] part was pacified. What has been said so far confirms that our map was made precisely for that purpose. The lines of the roads and the numbers representing distances added to them show this clearly, as also the fact that there are so many towns mentioned on it which are adjacent to the road lines drawn, next to other cities with well known names. The designer would not have added all these if he wanted to describe the provinces themselves, rather than the roads in them. He focussed on his own use.

[second column, right half of sheet 2]

228.5. He surpasses the surveyor, not the geographer. For this reason on must be aware not to attribute to the map an authority which the designer does not expect it to have, nor which it deserves on account of its ancient name. If anyone would hope for a useful application as is customary for geographical maps, collected in a devoted and scientific attitude, he is grossly in error. However, if someone forms the judgment that this map depiction has nothing to offer that cannot be found in the Itinerarium of Antoninus and the bare names found in it, he is equally in error. I think it is preferable to attribute an intermediate position to this map, considering it as a description to be used advantageously as the work of a designer whose efforts we intitially regarded as being rather coarse.

228.6. On the basis of the fragments I estimate the extension of this map as encompassing the Western empire with travel [indications] surpassing those of any other map. It is evident that only a small part has survived, and that there is more to be desired.

Rhenanus had already shown that the Rhine, from its mouth to its source had been fully described. But on these sheets he goes no further than Colonia Traiana [Xanten], although it extends further than that. Franciscus Irenicus reminds us of a certain Itinerarium Augustanum which is different from the Itinerarium of Antoninus. I think we are dealing with a revision of that map here. In that map you find, next to the many Rhine cities, also all cities of the Danube area, as many as were known in antiquity. He noted the names of a whole group of them, situated in Rætia, Noricum and Pannonia, all the way to Sirmium. On the sheets you see the remnants of the routes through Gallia, Britannia, Hispania and Africa. And Rætia [then] extended all the way to Italy, and Norica and Pannonia to Illyricum. However, the Western part, which Constantius and

[sheet 2, left page, column 1]

228.7. Galerius divided as regards the power, (being the first ones to do so, as Orosius says), comprised Italia, Africa, Hispania, Gallia Britannia and part of Illyricum. From the various separate parts of that empire traces can be derived indicating this, and therefore I do not regard it as doubtful that they, deplorably torn asunder as parts, were portrayed on the original. Thus it is the more regrettable and unpleasant that we have lost such a remarkable monument which, together with Antoninus and the Notitia Provinciarum, which could have contributed an incredible amount of information to illuminate and reconstruct the entire history of antiquity.

228.8. As regards the assessment of the antiquity of this map, I follow Rhenanus who believes it originated under the last emperors. There are many arguments to confirm this, and I will mention a few: the Franconian name that can be found on the first sheet only became known to the Romans at a rather late date, and is not mentioned in a text by anyone prior to Trebellius and Vopiscus. And those who think that Cicero already uses this name are seriously in error. They labour under the delusion of accepting the gloss in Iosephus about the Hebræans, Book 5, Chapter 42, saying that there were Germans and French people born from Franconians who were present at the burial of Herodes.

228.9. With the 'last emperors' I do not mean the last one who used the imperial name in the West, but those who as the last ones wielded power in the provinces that these travels refer to. To this reasoning I add, superfluously, that Theodosius the Great and his suns must be regarded as the last of the last. It cannot be that this description is later than Theodosius. For after the death of Theodosius, the barbarians under Honorius and Arcadius assumed power in various provinces, and soon in more. This becomes clear from the testimonies of historians.

[sheet 2, left page, column 2]

228.10. And because no one will be prepared to believe that the Romans described roads through provinces which had already been taken by barbarians, all that we have posited so far can be taken as facts. Of all the sheets, the sheet which we show first has been designed graciously and elegantly, the others are rather ridiculous and incomplete. And we would easily be able to do without the rest, if what they contain would have been incorporated on the first sheet, and if the place names would have been more clear, and if there was no need to read the other place names by way of comparison. Apart from the fact that different roads through Gallia, Hispania and Africa are not shown on the first sheet, the variants in the rest must also be compared.

228.11. These names have been mutilated seriously for many places - either because of inherent shortcomings of the map, or because of [errors introduced by] copyists, or a combination of both. For why would we deny that there are errors on this map? But that additional errors were introduced through copying is evident from the incompatibility between the first sheet and the rest. [This is] a forgivable incompatibility, because it seems to stem from obscure, dubious and lost letters as a result of their age in the manuscript. We have exerted ourselves with intense efforts to explain and reconstruct what the map could have looked like. The course of the [road] lines, through which watch-posts and quarters (for these are the terms used by surveyors) were connected with each other, pictures the course of public roads, which for reasons of a consular, pretorian and military nature were called roads.

228.12. Digest[arum] Lib[er] 43.tit.8.line 2. [the system of laws originating from Iustinianus] : Public roads are those roads which the Greeks call [in Greek lettering] Basilikas, kings roads, and what we call pretorian, others consular roads. They are called military roads in the same book (tit.7. line 3.), where their use is being described: Military roads run to the sea or to cities, or to public rivers, or to other military roads. These various types of junctions can be seen on our sheets. But not all public roads are comprised under these names. Ulpianus says with regards to the law we referred to before: Those who have been incorporated after the consular roads leading to estates or to}1624L/1641S}(to be continued on sheet 3, Ort 229).

|

Cartographica Neerlandica Background for Ortelius Map No. 228

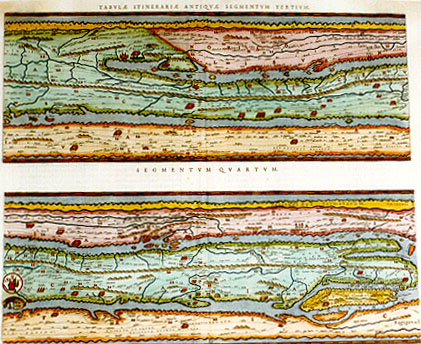

Title: none, see plate Ort 227. (this is the second sheet of the set of four, and contains segments three and four).

Plate size: (top:) 193 x 517 mm. (bottom:) 193 x 517 mm. (Firsdt state only:) D engraved at mid-bottom. Two (adjacent) maps on two plates.

Scale: not applicable.

Identification number: Ort 228 (Koeman/Meurer: 45P, not in Karrow, van der Krogt AN: 0910:2:31).

Occurrence in Theatrum editions and page number:

1619BertiusKK (200 copies printed) (this version includes the headings "à Marcomannis ad Sarmatas vqque. and à Sarmatis vsque ad Hamimaxobius". Further, the backside only says TABVLÆ PEUTINGERIANIÆ/SEGMENTVM III & IV.) see also below;

1624P/1641Sxliiij (1025 copies printed) (last line first text page, in two columns: respexit : Metatorem on Geogra- perium , ex quo Constantius & Galerius).

Approximate number of copies printed in the Theatrum: 1225.

States: 228.1 only. However, the text has three states:

-The first text state occurs in a few separately printed Peutinger maps of 1598. These sheets have no text on verso and no texts above the 8 map strips on the four map sheets Ort227-Ort230.

-The second text state occurs in Bertius' 1618/1619 atlas Theatri Geographiae Veteris Tomus Posterior, page KK, 1619, text: TABULÆ PEVTINGERIANA | SEGMENTVM III. & IV. Text above third map strip: TABULÆ PEVTINGERIANÆ SEGMENTVM III, "à Marcomannis as Sarmatas vsque". Text above fourth map strip: SEGMENTVM IV "à Sarmatis vsque ad Hamaxobios".

-The third text state occurs in the 1624Latin Parergon/1641 Spanish edition, but text in Latin, (last line first text page, in two columns: respexit : Metatorem on Geogra- perium , ex quo Constantius & Galerius). Text above third map strip: TABULÆ ITINERARIÆ ANTIQUÆ SEGMENTVM TERTIUM. Text above fourth map strip: SEGMENTVM QUARTVM.

Cartographic sources: see plate Ort 227.

Remarks: selection of cities in the third segment (from left to right): Sienna, Verona, Salzburg, Bologna, Tebessa, Bolsena, Ljubliana, Wien, Rimini, Ancona, Spoleto, Budapest. In the fourth segment a.o.: Roma, Carthago, Tivoli, Terracina, Split, Pozzuoli, Napoli, Pompei, Salerno, Palermo, Beograd, Tarente, Syracuse, Messina.

Bron: http:// www.orteliusmaps.com |

|

|

Cartographica Neerlandica Map Text for Ortelius Map No. 229

Text from the 1624 Latin Parergon edition, which is also used in the 1641 Spanish edition:

(sheet 3, right text page, column 1, a continuation of the Ort 228 text:)

229.1. {1624L/1641S{other settlements, even those, in my opinion, are public roads. I think that on the sheets not one single non-consular road, or, which is the same, not one non-military road has been drawn. I have established that these roads were paved in three different manners: they were covered with stones, or with pebbles, or with assembled earthen sods. Digest[arum] Lib[er] 43.tit.11.line 1. It is not allowed to make a road wider, nor longer, under the pretext of repair. He may either strew pebbles on an earthen road, or cover a road with stones where there used to be sods, or replace stones with sods. Yet, it seems that Isidorus connects a sods road with one of stones, when he says that an Agger is a road of average elevation, covered with assembled stones, called after agger which means heap, and which historians call a military road.

229.2. Undoubtedly, public roads are therefore aggers. Ammianus Marcellinus [says in] book 19: With a passable agger or a bridge placed above it, the area has been levelled. And in book 21, dealing with Iulianus: Impatient to wait, he travelled on public aggers, and since no one resisted him, he subdued the Succi. Rulers used to receive roads attributed to them, and Suetonius (chapter 37) confirms that Augustus established this practice. But Pomponius in his second book of About the origin of the Law attributes the origin of this practice to earlier times. I have established that individual roads were attributed to individual rulers, as shows from many [inscriptions in] stones.

229.3. Alternatively, one man took care of a multitude of roads. This is proved by a marble slate remaining in Auximum, which says that C[aius] Oppius, CVR[ATOR]. VIAR[VM]. CLODIÆ.ANNIÆ.CASSIÆ.CIMINÆ. TRIVM.TRAIANARVM.ET.AMERINÆ [i.e.] that he was attendant of the Clodian, Annian etc. roads. They were maintained by subcontractors, as Siculus Flaccus has written. Prisoners have also been condemned to carry out such maintenance, as you can read in Caius by Suetonius, chapter 27. They were marked by milestones, on which the number of miles was written, deriving their name from this. In an ancient inscription:

[sheet 3, column 2]

229.4. Milestones repaired. Even the emperor's name might be added, because they had commanded the repair. Coins of Augustus, ornated with arches, four-in-hands and insignia are similar examples: QVOD.VIÆ.MVN[ITÆ].SVNT, because roads have been maintained. Sidonius writes in his Propempt[ikon]:

Do not step on the Agger [elevated road]

From the surface of which, on antique tablets

Cæsars name flourishes.

229.5. Much is to be found in many writers concerning this view, and numerous stone tablets have survived as infallible witnesses. They provided the numeric information about distances which was entered in itineraries, and the same numbers can be found back in their mapsheets. It is only rarely that our numbers did not match those from the Itinerary of Antoninus, which is as it should be. For [remaining] mismatches I do not simply blame the negligence of the copyist. Unreliable as he may have been, mistakes can occur for a variety of reasons. Time itself is a cause of change. Some routes have been merged, when new shortcuts are found. Others change when detours become necessary. Next to that, Antoninus numbers always refer to the last camp.

229.6. Possibly, this is not consistent throughout the sheets, for I have myself observed milestones referring to the distance of some important city at a distance of one hundred miles or more, whereas intermediate cities of less importance are ignored. An example is a milestone in the vicinity of Oenipons [Innsbruck], on which Severus and his sons are inscribed. The distance to Augusta Vindelicorum [Augsburg], which is far away from there, is mentioned on these stones, [e.g.]: ROADS AND BRIDGES REPAIRED, FROM AUGUSTA ONE HUNDRED AND TEN MILES. And whatever is listed in a book in a fixed order, may on the mapsheets refer to the route to come or to the route already covered, for travelling in either direction is possible. The fact that at some camps two numbers have been entered suggests that they refer to different routes.

[left text page, first column]

229.7. For those who after all explanations still find what has been said very obscure and unworkable, [I want to say that] I have taken it upon me to oracle about matters which are so uncertain that my exertions may be judged as ridiculous. This is an honour which I gladly leave to others.

229.8. Judgment of the same Velserus, under a different name, about the same map, after he had obtained the whole series.

229.9. We present the map here, of which Marcus Velserus, Seven-man of the Republic of Augst, published the few sheets then available, under great applause from those who have literature on this subject close to their hearts. He then promised the entire series, if he could lay his hands on the manuscript; this could nowhere be found and it was feared that it had disappeared. But good fortune was benevolent to him, and Velserus has now made good on his promise. This message uplifted Abraham Ortelius, because what he had tried to achieve for more than twenty years in all sorts of ways, namely to publish it, now became his achievable task.

229.10. And it was a good choice that the other people interested in this left this task to this suitable candidate. Velserus was of the opinion that that the trust he had achieved with the public was best served if Ortelius was to bring the task of publishing them to completion, and therefore Ortelius was the first to be offered this map. After that, this man, in spite of his being over seventy years of age, who had more will power and more dedication than physical health, has deceased, while busy finishing this task.

229.11. Dying, commemorating his loved ones [quote from Ovidius' exile poetry], he left it in his will to his old friend Ioannes Moretus, who took it upon himself to finalise it on account of his dedication to the deceased. Velserus commented in a preface which he offered us to make, about its maker, antiquity, use and other matters concerning this map. To this we add: [second column]:

229.12. Its maker was a Christian. This appears clearly from the name of Saint Peter, and from what is related about Mozes and the Israelites. The size of the land the map represented could at the time not be assessed, except for the Western part of the Roman empire. It can now be determined that it covers more, namely the entire world as it was then known with certainty, depicting as it does the area from the very west to the very east, that is, between the pillars of Hercules and the altars of Alexander. And indeed, everything is represented on it, except what is outside the pillars: small parts are lacking of Britannia, Aquitania, Spain and Africa. All around lies the sea once called the Atlantic. We find information about maps for the purpose of travelling in the third book chapter six of Vegetius, which are certainly worth reading, and it seems probable that the History of Provinces as reported by P. Victor in the area of the Basilica Antoniana in the area of Flaminia is based on this.

229.13. As regards the nature of paving the roads, see Galenus' Methods, Book 9, Chapter 8. By way of explanation: the attitude of Velserus deserves to be continued, but this enterprise is difficult and takes long, and cannot be achieved by the industry of one single person. He cannot alone assume the task so eagerly awaited by the learned. Further, if this is of any importance: the manuscript is on parchment, consisting of carefully joined sheets, each of which is about one Augster foot wide, and the whole is about twenty-two feet long.

229.14. It seems that the designer found it most convenient to make it in these proportions. The letters used are written after the manner of the Longobardians, formed as they are with great effort. The designer uses Roman script. For the rest he makes a faithful representation, uncorrupted and in its entirety. He never allows himself to deviate, and never allows himself to remove the numerous and obvious mistakes occurring on the map, and never strays from his example. Nor of his own initiative, nor on the basis of existing knowledge, but simply by straining his eyes, [has he achieved this result]}1624L}. (Text to be continued on the last sheet, Ort 230).

|

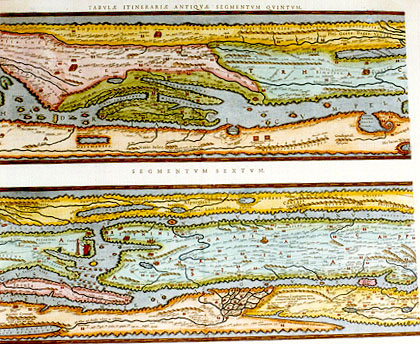

Cartographica Neerlandica Background for Ortelius Map No. 229

Title: none, see plate Ort 227. (This is the third sheet of the set of four, and contains segments five and six). (Low left:) "Hij montes subiacent paludi simili | Meotidi p. quem Nilus transit". [The mountains of Cyreneus. At the foot of these mountains there are swamps similar to that of Maeotis which is crossed by the river Nile]. (Bottom left:) Flo. Nilus qui diuidit Asiam et Libiam. [The river Nile which forms the border between Asia and Libia]. (Lower right:) Desertum i.u. quadraginta annis | errauert filij Isrl' ducente Moyse. "Hic legem acceperunt î monte Syna". [The desert in which the children of Israel roamed for forty years under the leadership of Mozes. Here they received the law near Mount Sinai].

Plate size: (top:) 193 x 518 mm. (First state only:) E engraved at mid-bottom. (bottom:) 193 x 517 mm. (First state only:) F engraved at mid-bottom. Two (adjacent) maps on two plates.

Scale: not applicable.

Identification number: Ort 229 (Koeman/Meurer: 46P, not in Karrow, van der Krogt AN: 0910:3:31).

Occurrence in Theatrum editions and page number:

1619BertiusLL (200 copies printed) (the backside only contains the text: TABVLÆ PEVTINGERIANÆ SEGMENTVM V. & VI. Further, the title of the lower strip there has been added: "à Sarmatis Roxulanis vsque ad Parnacos").

1624P/1641Sxlv (1025 copies printed) (last line first text page in two columns: men accepere. in vetusta Inscriptio- dicio est illas diuersa itinera respicere. | Qui- ; last line second text page, first column, full width: quæ nobis probantur. Addimus ; last line second column, full width: que maximè intendenti, id interdum | vsu ; text above map strip 5: TABVLÆ ITINERARIÆ ANTIQVÆ SEGMENTVM QVINTVM. Text above map strip 6: SEGMENTVM SEXTVM.).

Approximate number of copies printed in the Theatrum: 1225.

States: 229.1 only. Three text states, see above.

Cartographic sources: see plate Ort 227.

Remarks: selection of cities shown in the fifth segment (from left to right): Skopje, Olympia, Patras, Corinthe, Sofia, Sparta, Athene, Saloniki, Bengasi, Constantsa. In the sixth segment a.o.: Constantinople, Creta, Alexandria and Nile estuary, Ankara, Mount Sinai, Jerusalem, Jericho.

Bron: http:// www.orteliusmaps.com |

|

|

Cartographica Neerlandica Map Text for Ortelius Map No. 230

Text, translated from the 1624 Latin (Parergon) edition, also included in the 1641 Spanish edition; it is a continuation of the third mapsheet, Ort 229:

230.1. {1624LParergon/1641S{I have no doubt that this map has been used, and neither does anyone else doubt this, who is familiar with these kinds of medieval writings, in which it is often impossible to distinguish the difference between orthography of which the meaning and pronunciation are totally different from ours. Fare thee well, spectator, and the same to you, reader. Enjoy this monument of ancient times, which, although containing numerous inconsistencies, cannot be surpassed by anything similar yielded by antiquity.

230.2. From the writer to the reader.

230.3. Lest there remain any empty pages, I add the testimonies of Beatus Rhenanus, Gerard Noviomagus, and Franciscus Irenicus, which pertain to this travellers' map.

230.4. Beatus Rhenanus, German History, Book 1, about France.

230.5. Add to this what we saw on a regional map at our friend Chunradus Peutingerus in Augst, drawn during the reign of one of the last emperors, and found back by Celtis in some library or other, evidently of great antiquity, on which the following placenames have been written, from the mouth of the Rhine upwards: Carvo [Kesteren] xiii, Castra Herculis [near Arnhem] viii, Noviomagus [Nijmegen] vi, Burgiantium [Xanten] v, Colonia Traiana [near Xanten] xi, Vetera xiii, Asciburgium [Moers-Asberg] xiiii, Novesium [Neuss] xvi, Agrippina [Cologne], above the river Rhine, depicted by a line drawn from the right at the side of Germania mentioning the word FRANCIA. Near the mouth of the Rhine one can also read the following place names: chama vi qui elpranci, as also chauci. valpluarii. chrepstini.

230.6. From the same work, but now concerning the Germans.

230.7. Next it can be mentioned that on the road map which belongs to Chunradus Peutingerus, there is a depiction, across the Rhine above Tenedos, Iuliomagus [Schleitheim], Brigobannis [Hüfingen], and Aria Flavia , of a forest with trees, and added to that in capital lettering SYLVA MARTIANA [Woods of Mars], and above these words ALEMANNIA [Germany]. On the side, above the area of Borbetomagus [Worms] and Brocomagus [Brumath] it says SVEVIA [Bavaria].

[second column, last mapsheet]

230.8. But the designer put on the side of the forest what should have been put above it in showing this area, had not the limited size of the parchment prevented him from doing so.

230.9. From the third book, dealing with Gessoriaco [Boulogne].

230.10. Various conjectures have been made about this subject, but the military map which we inspected at our friend Chunradus Peutingerus in Augst contains an ambiguity. On it there has been written: Gessoriaco now called Bononia [Boulogne]. But what is meant is Bononia Maritimam [Boulogne at the sea].

230.11. Gerardus Noviomagusfrom his History of the Bataves:

230.12. Gorchemus [Gorinchem], not far from Castra Herculis [near Arnhem], is one of the villages which together with those around it maintains its name to the present day. This area, called Herculis, is in the language of the Bataves called Dat landt van Arckel, [the land of Arkel]. On the extremely old map showing Roman military roads in various regions, mention is made of fortifications in this area. The distinguished lord Chunradus Peutingerus, a well respected scholar, patrician and honorable member of the council of Augst, who, assisted by Celtis, the celebrated poet, having begun to describe his native country of Germany, showed it to me.

230.13. Franciscus Irenicus, from his Exegeses of Germany, Book 9, Chapter 6:

230.14. Bingum, Bingen. This is what is mentioned by Tacitus, Ptolemæus, Antoninus and on the Augst map. Antonius and the Augst Map make mention of the city of Sacarbantia, that is, Sankt Pulten [Sankt Polten] which Antoninus in his Itinerarium Augustanum mentions. Savaria stands for Stein an den Angern and not for Gretz, as some want to make us believe, as testified by Antoninus, Ptolemæus and in the Augustan Itinerary. I am certain that Ptolemæus as well as the Augst map designate Lechsmind as Artobriga [Weltenburg], not as Ratisbona [Regensburg]. Teutoburgus stands for Seva, where the river Daros empties into the Danube. This place is referred to by Ptolemæus, Antoninus and the Augster Road Map. Sirmium [Sremska Mitrovica] stands for Agria, both in Antoninus and in the Augst road map.

230.15. [Irenicus] Same title, same book, Chapter 7.

230.16. Lately, we could lay our hands on a certain road map which, although old, reached us very quickly. It is called the Augster road map, for it is said to have been retrieved there.

[first colum second text page fourth mapsheet]

In it, one finds cities in the area of the Danube, as many as were known in antiquity. Some names of German cities are to be found on it, but very unclear, and with consideration and care we bring it to light here. Regelspurg [Regensburg] is here first called Rhegino. Patavium [Padua] was once Castellum Bolodorum. Then, there was the monastery of Lampach, not far from the river Draos, called Ovilia on the map, as well as in the Itinerary of Antoninus where it is called Ovilabis. Carnunto must be identified with Peternel, close to Namburgus, we think. Also, Taurinus is called Moesia Superior on it, we have the impression. Vetomanis corresponds with Pettau, or a place close to Petavio.

230.17. A little further, where he describes Pannonia Superior, he reminds us of Petavio. It seems that Kingsfeld derived its name from Vindonissa [Windisch]. Selestadius is sometimes called Hellus, at other times Helvetus, words also used by Antoninus. Pontus Saroi, to continue, is called Sarbruck [Saarbrücken].

[second column left text page fourth mapsheet]

Argentaria is Colmar. Tabernis is Zabern [Saverne]. Matricorum is Metz. Argentorace is Argentinam [Strassbourg]. Aventicam is Habelspurg . Iuvaniam is Salzburgam [Salzburg]. Solidurnum is Soldurn [Solothurn], at least, this is our best guess.

230.18. Ptolemæus and Antoninus use these names repeatedly. Further, the map contains a number of place names which have retained their original name. Among those are Colonia [Cologne], Argentorace [Strassbourg], Iuliacum [Jülich], Flevio, Novesum [Neuss], Bingium [Bingen], Asciburgum [Moers-Asberg], Noviomagum [Nijmegen], Augusta Trevirorum [Trier], Augusta Rauricorum [Basel/Augst], Confluentia [Koblenz], Bonna [Bonn], Rigomagus [Remagen], Moguntiacum [Mainz], Bregetomagum, Augusta Lyci, Aris Flavis [Rottweil], Lacus Brigantinus [Bodensee], Sirmium [Sremska Mitrovica], Mursa [Osijek], Ponte Drusi [Scharnitz], Brigantia, Ulmo [Ulm], and the names of other cities which continue to exist till this day. We can add to this that we can vouch for their antiquity, and that we can determine that they are the oldest cities of Germany. Other matters concerning this map we lay aside, leaving them to the further attention of our successors}1624LParergon/1641S end here}. |

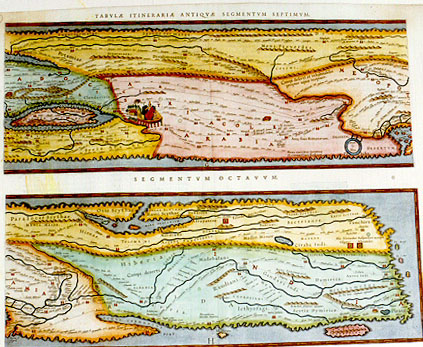

Cartographica Neerlandica Background for Ortelius Map No. 230

Title: none, see plate Ort 227. (This is the fourth sheet of the set of four, and contains segments seven and eight). (Upper right:) Campi deserti et inhabitabiles. | propter aquæ inopiam. [These fields are deserted and uninhabited because of lack of water]. (Upper right:) Areæ fines Romanorum. [The borders of the Roman army.] (Upper right:) Fines exercitus Syriaticæ | et commertium Barbaror. [The border of the Syrian army and of commerce with the barbarians]. (Lower right:) Hic Alexander Responsum accepit | vsque quo Alexander. [Here Alexander the Great received his answer. This is how far Alexander went.] (Lower right:) "In his locis scorpiones nascuntur". [Here scorpions live]. (Lower right:) "In his locis elephanti nascuntur". [In these regions live elephants].

Plate size: (top:) 192 x 517 mm. (First state only:)G engraved at mid-bottom. (bottom:) 194 x 516 mm. (Fist state only:) H engraved at mid-bottom. Two (adjacent) maps on two plates.

Scale: not applicable.

Identification number: Ort 230 (Koeman/Meurer: 47P, not in Karrow; van der Krogt AN: 0910:4:31).

Occurrence in Theatrum editions and page number:

1619BertiusMM (200 copies printed) (On the backside the only text is: TABVLÆ PEVTINGERIANÆ SEGMENTVM VII. & VIII. Above the 7th strip the following text: TABULÆ PEVTINGERIANÆ SEGMENTVM VII. "à Parnacis vsque Paralocas Scythas". Above the 8th strip the text: SEGMENTVM VIII. "à Paralocis Scythis vsque ad finem ASIÆ".) Note that in Bertius this map is followed by a single ninth strip on a single folio mapsheet, showing Netherlands and a part of South-East England.),

1624P/1641Sxlvj (1025 copies printed) (last line, in two columns, first text page: S V E V I A. Augustanum vocabant, vbi repertum fuisse dixe-). Text above 7th map strip: TABVLÆ ITINERARIÆ ANTIQUÆ SEGMENTVM SEPTIMVM. Text above 8th map strip: SEGMENTVM OCTAVVM.

Approximate number of copies printed: 1225.

States: 230.1 only, but three text versions, see above.

Cartographic sources: see plate Ort 227.

Remarks: selection of cities in the seventh segment (from left to right): Damascus, Cyprus, Antioch, Aleppo, Arabia, Colchi, Mesopotamia. In the eighth segment a.o.: Babylon, Caspian sea, Persepolis, island of Ceylon, river Ganges.

Bron: http:// www.orteliusmaps.com |

|

|

|

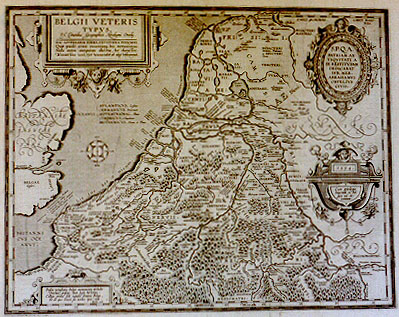

Abraham Ortelius, Belgii Veteris Typus, 1594 (detail). |

|

|

Cartographica Neerlandica Background for Ortelius Map No. 197 (Replaced by No. 198)

Text, translated from the 1584L 3rd Add., 1584 Latin, the 1584 German 3rd Add., 1585 French 3rd Add., 1587 French and the 1592 Latin editions:

197.0. {1587F only{Parergon to the Theatre.

Although it seems that the maps now following do not in any way serve our purpose, which was to include in our Theatre the locations of places and areas as they are at present, yet, in response to request from various friends of mine, and to please the lovers of ancient history, both sacred and profane, I have wanted to add them here in this part, at the end of this work, as an accessory work}1587F only}.

197.1. {1584L3Add{BELGIUM {1584G3Add has instead{Netherlands}1584G3Add instead}{1585F3Add & 1587F instead{Belgian Gallia}1585F3Add & 1587F instead}.

197.2. The word Belgium which Cæsar uses more than once or twice in his De bello Gallico [About the French War] has for a long time and often troubled readers {1584G3Add has instead{the learned}1584G3Add instead}. For some of them think that Cæsar referred to a city, which some, including Guicciardini and Marlianus) interpret to be BEAUVAIS in France, others BAVAYS in Henault. To the latter group belong Blaise Vigenereus {1585F3Add & 1587F only{of Bourgogne}1587F only} and the chronicles of our own low countries. The learned Goropius thinks that the Bellovaci, a people of this area {1585F3Add & 1587F have instead{those of Beauvoisin}1585F3Add & 1587F instead} were meant by it. There are some who think that Cæsar used Belgium for Belgica, just as Livius uses Samnium for the country of the Samnites. {not in 1584G3Add{This was the opinion of Glareanus. Ioannes Rhellicanus says that it contained part of Gallica Belgica, but which part that should be, he does not say.

197.3. Hubertus Leodius claims it to be that part which is now near Henault, where the [city of] BAVAYS just mentioned is now situated}not in 1584G3Add}. But leaving these opinions for what they are, let us hear what Cæsar himself has to say about this Belgium. In his fifth book, where he speaks of the distribution of the legions in Belgica, he uses these words: Of whom he committed one to Quintus Fabius, the legate, to be led against the Morini {1585F3Add & 1587F have instead{the land of Terouënne}1585F3Add & 1587F instead}. another to Quintus Cicero against the Nervij {1585F3Add & 1587F have instead{Tournay}1585F3Add & 1587F instead}, the third to L. Roscius against the Essui. The fourth he commanded to hibernate, with Titus Labienus {not in 1584G3Add{in Reims}not in 1584G3Add}, in the confines of Trier. Three he placed in Belgium. Above these he set as commanders Marcus Crassus the treasurer, and Lucius Munatius Plancus and Caius Trebonius the legates.

197.4. One legion which he had taken up from just beyond the Po with five cohorts, he sent against the Eburones {1585F3Add & 1587F instead{the land of Liège}1585F3Add & 1587F instead}. And a little earlier in the same book, where he speaks of Britannia, you shall find these words: The sea coast of Britain is inhabited by those who for plundering and war went from Belgium to it, {1585F3Add & 1587F only{Vigenereus interpretes this as the higher Belgium}1585F3Add & 1587F only} all of them mostly called by the names of those cities where they were bred and born. Here it appears very clearly for the first time that Cæsar under the name Belgium takes not just one city, but many. Also, that he does not refer to all of Belgica, seeing that he mentions the Morini, Nervij, Essui, Rheni and Eburones {1585F3Add & 1587F have instead{those of Terouënne, Tournay, the Essui, those from Liège and of Reims}1585F3Add & 1587F instead}, all of which nations he himself, as well as other good writers, attributes to Gallia Belgica. Therefore it is clear that Belgium is a part of Belgica, but which part it should be is not so clear.

197.5. That it is not in the area of Bavacum (BAVAIS) in Henault, {1584G3Add, 1585F3Add & 1587F only{as Thomas Leodius claims}1584G3Add, 1585F3Add & 1587F only}, is manifest because that [city] is situated among the Nervij {1585F3Add & 1587F have instead{Tourneses}1585F3Add & 1587F instead} which Cæsar himself excludes from Belgium. Neither can I be persuaded that it was near the Bellovaci {1585F3Add & 1587F have instead{Bauvoisins}1585F3Add & 1587F instead}, but rather that it was part of Belgica, which is closer to the sea and which lies further up to the North, namely, where the three great rivers Rhine, Maas and Schelde meet and fall into the main ocean. These afford an easy passage and where they fall into the sea, it is only a short journey to Britain. Moreover, it is most likely that they should take the sea route with which they were familiar and acquainted, and they lived on the shores and banks of these rivers, in contrast to those who dwelt higher up into the country, to whom the sea was more threatening. They therefore who went from Belgium to Britain only exchanged one coast for the other.

197.6. About the origin and reason for the words Belgium and Belgica the opinions of various writers also differ. There are some who derive it from BELGEN or WELGEN, a word of our own [language] which means stranger. Another man of great learning and judgment fetches it from BELGEN or BALGEN, signifying to be angry, to fight. Our chronicles claim it to be named as it is after Belgis, the chief city of this province. Neither do they agree about the location and place of it. For one of them places it at Bavais, a town in Henault, another at VELTSICK, a village near Oudenaarde. {not in 1584G3Add{They who think the name comes from the city of Belgis (which is not found elsewhere in the writings of any good author, either a geographer or a historian) refer to}not in 1584G3Add} Isidorus in the 4th chapter of the 13th book of his Origines {not in 1584G3Add{as their example, where he writes like this: Belgis is a city in Gallia from which the province Belgica took its name}not in 1584G3Add}.

197.7. The same is found {1585F3Add & 1587F only{before Isidorus}1585F3Add & 1587F only} in Hesychius' [in Greek lettering:] Belgaios apo poleoos Belgas, that is, Belgi was so named after the city of Belges}not in 1584G3Add}. Iustinus in his 24th book cites{not in 1584G3Add{from Trogus Pompeius}not in 1584G3Add} one Belgius, a captain of the Gauls, from whom it is likely that they took the name {not in 1584G3Add{if you believe Berosus or rather Pseudoberosus. For he writes: {not in 1585F3Add & 1587F{Beligicos (sive Belgicos) appellari à Beligio (aut Belgio) Celtarû rege}not in 1585F3Add & 1587F} [that is] The Beligici or Belgici were so named after Beligius (or Belgius), a king of the Celts}not in 1584G3Add}. Well, let us leave this to the censure of the learned}1587F ends here}, and proceed to certain testimonies of ancient writers {1584G3Add only{about Belgica}1584G3Add only}{not in 1584G3Add{which we think will be both pleasant}not in 1584G3Add}.

197.8. Cæsar in his first book of the wars in France [speaks like this:] All GALLIA is divided into three parts, of which the Belgæ inhabit one, the Aquitani another. The third [is inhabited] by those who in their own language are called Celtæ, but in Latin Galli. Of all these, the Belgæ are the most hardy because they are further away from the manners and culture [typical] of this province, and because they have no traffic with merchants or others who bring those things which effeminate men's minds, and also because they are neighbours to the Germans who dwell beyond the Rhine, with whom they wage war continually.

197.9. {not in 1584G3Add{The Belgæ dwell in the outskirts of Gallia. They belong to that part which is within the lower part of the river Rhine. They are on the North and East sides of it}not in 1584G3Add}. The same author in his second book has these words: Cæsar found that many of the Belgæ came from the Germans, having long ago traversed the Rhine and having settled themselves there because of the great fertility of the area, that they had driven out the Gauls, who formerly had dwelled there. And that these were the only men who in the days of our fathers, all Gallia being sorely troubled, had prevented the Teutones and Cimbres from entering within the bounds of their territories, after which it came to pass that the memory and record of these famous deeds have made them proud and conceited because of their great power and skill in martial affairs.

197.10. {not in 1584G3Add{In the 9th book of Hirtius [we find] The Belgæ, whose courage was great}not in 1584G3Add}. Strabo, in the 4th book says The Belgæ wear cassocks or cloaks, their hair [is] long and they wear side breeches. Instead of coats or jerkins they use a kind of sleeved garments, hanging down to their waist or as low as their buttocks. Their wool is very coarse and rough, yet has been cut close to the skin. Of that they weave their coarse, thick cassocks which they call lænas, rugs or mantles.

197.11. Their weapons are in proportion to their height and consist of long swords, hanging by their right side, a long shield, lances to measure, and a javelin, a kind of short pike with a barbed head. Some use bows and slings, others have a wooden staff like a dart which they do not cast with a loop but with the hand only, and further than one can shoot an arrow. They use this especially in hunting and fowling.

197.12. They are all used to lying on the ground, even to this day. They dine and take supper sitting on matrasses {1584G3Add instead{heaps of brushwood}1584G3Add}. Their food generally consists of milk and all kinds of meat, especially pork, both fresh and salted. Their hogs lie out in the field night and day. In size, strength and swiftness of feet they surpass those of other countries, and if a man is not used to them, they are as dangerous as a wolf.

197.13. They build their round houses of boards, planks and rafters, covered by a large roof. They have so many and excellent herds of cattle and hogs that they do not only provide Rome with those cassocks just mentioned, and with salted bacon, but also many other places in Italy. Most of their cities and regions are governed by the nobility and gentry. In former times the common people yearly used to elect one prince, and one general captain for the army. They are mostly subject to the command of the Romans.

197.14. They have a kind of custom in their councils which is specific to themselves [only]. If any man interrupts or troubles another, the sergeant will come to him with a bare knife in his hand and commands him to keep quiet. This may be repeated a second and third time. If [the offender] will still not be quiet, so much of his cassock will be cut off that the remainder is no longer of any use.

197.15. They have in common with many other barbarous nations that the services of men and women are requested in a way which is quite different from the customs and manners we use here. {not in 1584G3Add{The nearer the Gauls are to the North and to the sea, the more brave they are. The Belgæ are particularly to be recommended, divided as they are into 15 nations, so that the Belgæ alone sustained the assault of the Germans, Cimbers and Teutones. What an infinite number of men they were able to put together may here be understood because they enlisted a long time ago as many as 30,000 Belgæ, only [consisting of] able men, fit for war.

197.16. There are some who divide the Gauls into three nations, namely the Aquitani, Belgæ and Celtæ. The Belgæ possess the places near the sea, even as low as the mouth of the Rhine}not in 1584G3Add}. Diodorus Siculus in his 5th book [says:] A nation mostly inhabiting those places towards the North. It is a cold country so that in winter time instead of water it is all covered with deep snow. The ice also, in this country, is so heavy and thick and their rivers are frozen so thoroughly that they may be walked on, not only by a few, but even by whole armies with horses, carts and luggage.

197.17. Plutarchus in his Life of Cæsar [says:] But after that, news reached us that the Belgæ, the most mighty and war-like nation of the Gauls, who possessed the third part of all Gallia had gathered many thousands of armed men, he attacked them with all possible speed &c. Appianus in his history of France [says:] Cæsar quickly directing his army against the Belgæ at a narrowing of the river slew so many of them that the heaps of dead bodies served as a bridge. {not in 1584G3Add{Ammianus in the 15th book of his history [says:] Of all the Gauls the ancients considered the Belgæ to be the most valiant and stout, because they were far from those who lived more court-like and comfortable. Neither were they corrupted or effeminated with foreign delicacies, but they were fully exercised in wars against those Germans who dwelt beyond the Rhine.

197.18. Florus in his 3rd book [says:] The next was a far more cruel battle against the Belgæ, for then they fought for their liberty}not in 1584G3Add}.

197.19. Plinius in the 20th chapter of his 35th book [says] In the province of Belgica they cut a kind of white stone with a saw (as they do more easily for wood) to make slates and tiles as coverings for their houses, to serve as roof tiles, {not in 1584G3Add{and when they like, as those kinds of coverings which they call pavonacea like a peacock's tail, in such a manner as they may be sawed}not in 1584G3Add}. {1584G3Add only{Near Rome, at Gentile Delphinio, one finds a fragment of an ancient column Licinij Suræ which mentions these peoples and their land. The same is true for Graitz in Styria and in Naples}1584G3Add ends here}. {1584L{Again, Plinius in the 36th chapter of his 16th book: The Belgæ stamp the tufts of this kind of reed and put them between the joints of ships to seal them as with pitch and tar. {1592L{In the first chapter of his twelfth book he says that The plane tree has come now as far as the Morini, into a tributary soil, so that these nations may pay customs even for their shade. In the 25th chapter of the 15th book: In Belgia and on the banks of the Rhine the Portugal cherries are most esteemed. In the 14th chapter of the same book, where he speaks of various kinds of apples: which, since they have no kernels, are called by the Belgæ spadonia poma{[spade apples].

Ausonius about the river Gebbe which empties into the Mosella: Its turnings results in many round pebbles, while it makes its sawing noise between its marble banks. Silius Italicus in book 10: As when a Belgian dog chases hidden boars, he searches cunningly by nose the meandering tracks of the wild beasts in hidden and untrodden areas}1592L}.

197.20. In Vergilius' Georgics 1 [in fact 3, 204], we find: or he will with an obedient neck pull the Belgian chariots}1585F3Add & 1592L end here} {1584L3Add & 1584L only{and in Lucanus' first book [§426] the Belga, a docile driver of the scythe chariot.

A fragment of a pillar base in Rome at Gentile Delphinio of Licinius Sura, where you can read:

EMPEROR CAESAR. ///////////////////////////////////////// DACICUS [honorary title granted after his victory in Dacia]. HAS SUBDUED THE DACIANS AND THEIR KING DECEBALVS IN WAR UNDER THE SAME COMMANDER AS A LEGATE WITH THE RANK OF PRAETOR AND TO THE SAME HAVE BEEN GRANTED: 8 LANCES WIHOUT IRON SPIKES [donated as a sign of their bravery], 8 STANDARDS, 8 WALL WREATHES [a sign of honour for who first climbed the wall when storming the city], 2 WALL WREATHES, 2 FLEET WREATHES, 2 GUILDED WREATHES, 2 LEGATES [in the rank of praetor] OF THE BELGIAN PROVINCES, A LEGATE OF THE LEGION, 1 MINERVA, CANDIDATE FOR THE RANK OF CAESAR IN THE PRETORIAN AND IN THE TRIBUNATE OF THE PEOPLE, AND QUAESTOR OF THE PROVINCE OF ACHAIA, MEMBER OF THE COMPANY OF FOUR OVERSEEING THE ROADS. THE SENATE HAS DECIDED ON THE RECOMMENDATION OF EMPEROR TRAIANUS AUGUSTUS GERMANICUS DACICUS TO AWARD THE TRIVMPHAL ORNAMENTS AND HAS DECIDED TO ERECT A STATUE AT PUBLIC EXPENSE.

197.21. In Graecius (vulgarly Graitz), a city in Styria:

TO TITUS VARIUS CLEMENS, BECAUSE OF THE LETTERS OF THE AUGUSTI, PROCONSUL OF THE PROVINCES OF BELGICA AND BOTH [upper and lower] GERMANIES, RAETIA, [and] MAURETANIA, BELONGING TO THE EMPIRE, LVSITANIA, CILICIA, LEADER OF THE BRITISH TROOPS OF A THOUSAND HORSEMEN, 2 LEADERS OF AUXILIARY CAVALRY TROOPS IN TINGI IN MAVRETANIA, SENT FROM SPAIN, 30 TROUPS OF PANNONIANS, ULPIA, 2 PREFECTS OF THE COHORT OF THE MACEDONIAN GAULS.

THE CITY OF THE TREVIRI [Trier], FOR THE EXCELLENT LEADER.

197.22. [In] Naples:

TO PUBLIUS AELIUS, SON OF PUBLIUS AGRIPPINUS, HORN-HOLDING [sign of honour] PROCONSUL OF THE PROVINCE OF BELGICA, MOST BELOVED AND AMIABLE BROTHER TO AELIA, [erected] BY HER DEVOTED MOTHER. VICTORINUS, A MAN FREED BY AUGUSTUS, HAS MADE THIS}1584L3Add & 1584L only}.

{1584L3Add, 1584L & 1592L only{A silver coin of mine.

[Two sides of a coin are shown, one with a rider on horseback with SER.GALBA IMP, the other with three portraits, all facing right, with TRES GALLIAE].

The placenames which you can read on this map have been published in our Thesaurus Geographicus}1584L3Add, 1584L & 1592L only, which end here}.

|

Cartographica Neerlandica Background for Ortelius Map No. 197 (Replaced by No. 198)

Title: BELGII VETERIS | TYPVS | "Ex conatibus geographicis Abrahami Ortelij". [A map of the ancient low countries, from the geographical efforts of Abraham Ortelius.] | HAC LITTERARVM FORMA, VETVSTIORA PINXIMVS. | Quæ paulo erant recentiora, his notauimus. | "Nulla autem antiquitate illustria, hoc charactere | Recentissima vero, his vernaculis ab alijs distinximus" [With this type we recorded the oldest [Roman] names [CAPITALS]. Those of later times with this type [lower case]. Names that do not derive from antiquity with this type [cursive lower case]. While for modern names we use this type [cursive fantasy font] to distinguish them from the others].(Oval cartouche upper right:) S[enatus].P[opulus].Q[ue].A[ntwerpiensis]. | PATRIAM AN:|TIQVITATI A SE | RESTITVTAM | DEDICABAT | LVB. MER. | ABRAHAMVS | ORTELIVS | CIVIS. (Around edge of cartouche:) NESCIO QVA NATALE SOLVM DVLCEDINE CVNCTOS DVCIT, ET IMMEMORES NON SINIT ESSE SVI. (Quote from Ovidius' "Ex Ponto 1,3,5). [With pleasure the citizen Abraham Ortelius dedicates this map of his native country to the senate and people of Antwerp; I do not know what has a sweet hold on all the native soil; it does not tolerate oblivion]. (Cartouche lower right:) "1584 | Cum priuilegio | Imperiali et Bel:|gico, ad de:|cennium". [With an imperial and Belgian privilege for ten years]. (Cartouche left bottom:) "Prisca vetustatis Belgæ monumenta recludit | Ortelius, priscas dum legit historias. | Collige prima soli natalis semina Belga, | Et de quo veteri sis novus ipse vide. | Favolius caneb". [By studying books on ancient history, Ortelius rediscovered the antique monuments of the Low Countries in Roman times; Collect, reader, the first grains of your native soil, and learn from which ancestors you are the offspring. From the poetry of Favolius] (a personal friend of Ortelius, physician and poet).

Plate size: 377 x 492 mm.

Scale: 1 : 1,400,000

Identification number: Ort 197 (Koeman/Meurer: 6P, Karrow: 1/154, vdKrogtAN: 3000H:31A).

Occurrence in Theatrum editions and page number:

1584L3Addblank or * (100 copies printed) (identical to 1584L, but here without page number; last line, centred, in cursive script: "Vocabulis locorum,quæ in hac tabula legentur,lucem dabit noster Thesaurus Geographicus".),

1584L101 (or occasionally 103) (750 copies printed) (identical with 1584L3Add, but here with page number; last line, centred, in cursive script: "Vocabulis locorum,que in hac tabula legentur,lucem dabit noster Thesaurus Geographicus".),

1584G3Add16 in upper right corner (75 copies printed) (last line, left aligned, in Gothic script: zu Graitz in Styrien/und zu Neaples.),

1585F3Add11 (75 copies printed) (last line, left aligned, after 3. in cursive script: "Virgile en ses Georg.liure 3. Mieux trainera aux affaires belgiques Le col domté,les chariots Belgiques".),

1587F101 (250 copies printed) (last line, left aligned: Belgium roy des Celtes. Nous laisserons ces choses à debatre à qui bon semblera.),

1592L6 (525 copies printed) (last line, left aligned, partly in cursive script: Virgilius Georg.1. "Belgica vel molli meliùs feret esseda collo". Lucan.lib.1. "Et docilis rector rostrati Belga couini".).

States: 197.1 as described.

197.2: in 1592 some place names were added and one place name was changed: along the coast lower left added: GESSORIACVS | PAGUS; centre: Quarta; low centre: AD FINES, and "Andagium"; right of centre: CORIOVALLVM, RUMANEHA and "Belsonancum. Cauburg" was replaced by CASTRA SARRÆ.

Approximate number of copies printed: 1775.

Cartographic sources: made by Ortelius on the basis of classical sources. The ones he mentions, notably Cæsar, deal with peoples and names, rather than with the geography of the area.

References: H.A.M. van der Heijden "Ortelius and the Netherlands", p. 271-290 in: M. van den Broecke, P. van der Krogt and P. Meurer (eds.) "Abraham Ortelius and the First Atlas", HES Publishers, 1998. H.A.M. van der Heijden "Old Maps of the Netherlands", 1548-1794, Canaletto, Alphen aan de Rijn, Netherlands, 1998, map 28, p. 200-202; H.A.M. van der Heijden (2004) "De bataafse mythe in de cartografie", in "Caert-Thresoor" 23.2, p. 37-41.

Remarks: This map was replaced in 1595L by plate Ort 198 which bears the date 1594.

Bron: http:// www.orteliusmaps.com

Zie hierna: Abraham Ortelius en de kaart van de Nederlanden in de Romeinse tijd. |

|

|

Cartographica Neerlandica Map Text for Ortelius Map No. 198

Text, very similar to that of Ort197, translated from the 1595 Latin, 1601 Latin, 1602 German, 1603 Latin, 1606 English, 1608/1612 Italian, 1609/1612Latin/Spanish & 1624 Latin Parergon/1641 Spanish [but text in Latin] editions:

198.1. {1595L{BELGIVM{1602G & 1606E have instead:{THE LOW COUNTRIES}1602G & 1606E instead}

198.2. The word Belgium which Cæsar uses frequently {not in 1606E{in his French Wars}not in 1606E} has for a long time and often troubled readers {1602G instead{scholars}1602G instead}. For some of them think that Cæsar referred to a city, which some (including Guiccardini and Marlianus) interpret to be BEAUVOIS in France, others BAVAYS in Henault. To the latter group belong B. Vigenereus and our own fatherlands chronicles. The learned Goropius thinks that the Bellovaci, a people of this area were meant by it. There are some who think that Cæsar used Belgium for Belgica, as Livius uses Samnium for the country of the Samnites. {not in 1602G{This was the opinion of Glareanus. Ioannes Rhellicanus says that it contained part of Gallica Belgica, but which part that should be, he does not say.

198.3. H. Leodius claims it to be that part which is now near Henault, where the [city of] BAVAYS just mentioned is now situated}not in 1602G}. But leaving these opinions for what they are, let us hear what Cæsar himself has to say about this Belgium of his. In his fifth book, where he speaks of the distribution of the legions in Belgica, he uses these words: Of whom he committed one to Quintus Fabius, the legate, to be led against the Morini, another to Quintus Cicero against the Nervij. the third to L. Roscius against the Essui. The fourth he commanded to hibernate, with Titus Labienus {not in 1602G{in Rheims}not in 1602G}, in the confines of Triers. Three he placed in Belgium. Above these he set as commanders Marcus Crassus the treasurer, and Lucius Munatius Plancus and Caius Trebonius the legates.

198.4. One legion which he had taken up just beyond the Po with five cohorts, he sent against the Eburones. And a little earlier in the same book, where he speaks of Britannia, you shall find these words: The sea coast (of Britain he means) is inhabited by those who for plundering and war went from Belgium to it, all of them mostly called by the names of those cities where they were bred and born. Here it appears very clearly for the first time that Cæsar under the name Belgium takes not just one city, but many. Also, that he does not refer to all of Belgica {1606E only{Gallica}1606E only}, seeing that he mentions the Morini, Nervij, Essui, Rhemi and Eburones, all of which nations he himself, as well as other good writers, attribute to Gallia Belgica. Therefore it is as clear as daylight that Belgium is a part of Belgica, but which part it should be is not so clear.

198.5. That it is not in the area of Bavacum (BAVAIS) in Henault, as Leodius claims, is manifest because that [city] is situated among the Nervij which Cæsar himself excludes from Belgium. Neither can I be persuaded that it was near the Bellovaci, but rather that it was a part of Belgica, which is closer to the sea and which lies further up to the North, namely, where the three great rivers Rhine, Maas and Schelde meet and fall into the main ocean. These afford an easy passage and where they fall into the sea, it is only a short journey to Britain. Moreover, it is most likely that they should take the sea route with which they were familiar and acquainted, and they lived on the shores and banks of these rivers, in contrast to those who dwelt higher up into the country, to whom the sea was more threatening and terrible. They therefore who went from Belgium to Britain {1608/1612I only{or England}1608/1612I only} only exchanged one coast for the other.

198.6. About the origin and reason for the words Belgium and Belgica the opinions of various writers differ. There are some who derive it from BELGEN or WELGEN, a word of our own [language] which means stranger. Another man of great learning and judgment fetches it from BELGEN or BALGEN, signifying to be angry, to fight. Our Belgian chronicles claim it to be named as it is after Belgis, the chief city of this province. Neither do they agree in the location and place of it. For one of them places it at Bavais, a town in Henault, another at WELTSICK, a village near Oudenaarde. They who think the name comes from the city of Belgis (which is not found elsewhere in the writings of any good author, either a geographer or a historian) refer to Isidorus in the 4th chapter of the 13th {1624LParergon/1641S have instead{14th}1624LParergon/1641S instead} book of his Origines as their example, {not in 1602G{where he writes like this: Belgis is a Gaul city from which the province of Belgica took its name}not in 1602G}.

198.7. {not in 1608/1612I{The same is found in earlier in Hesychius' {1606E only{the Greek [who came] before him, in his Lexicon}1606E only} {not in 1602G{[in Greek lettering]: Belgaios apo poleoos Belgas}not in 1608/1612I}, {1606E only{that is, Belgy was so named after the city of Belges}1606E only}, as Honorius also says in his image of the world}not in 1602G}. Justinus in his 24th book cites {not in 1602G{from Trogus Pompeius}not in 1602G} one Belgius {not in 1602G{(Pausanias calls him Bolgius)}not in 1602G}, a captain of the Gauls, from whom it is likely that they took the name {not in 1602G{if you believe Berosus, or rather Pseudoberosus. For he writes: Beligicos (sive Belgicos) appellari a Beligio (aut Belgio) Celtarum rege {1606E & 1608/1612I only{[that is] The Beligici or Belgici were so named after Beligius (or Belgius), a king of the Celtes}1606E & 1608/1612I only}. About the region of Belgis we have written in our geographical Treasury. Well, let us leave this to the censure of the learned, and proceed to certain testimonies of ancient writers which we think will be pleasant}not in 1602G} {1606E only{and profitable to the student of chorography}1606E only}.

198.8. Cæsar in his first book of the wars in France speaks like this. All of GALLIA is divided into three parts, of which the Belgæ inhabit one, the Aquitani another. The third [is inhabited] by those who in their own language are called Celtæ, but in Latin Galli. {1606E only{Again, a few lines later:}1606E only} Of all these, the Belgæ are the most stout and hardy because they are further away from the quaint behaviour and manners [typical] of this province, and because they have no traffic with merchants or others who bring in those things which effeminate men's minds, and also because they are neighbours to the Germans who dwell beyond the Rhein, with whom they wage war continually.

198.9. {1606E only{The same [author] on the same page thus describes the location of their country}1606E only}. {not in 1602G{The Belgæ dwell in the outskirts of Gallia. They belong to that lower part which is within the river Rhine. They are on the North and East sides of it}not in 1602G}. The same author in his second book has these words: Cæsar found that many of the Belgæ came from the Germans, having long ago traversed the Rhine and having settled themselves there because of the great fertility of the area, and that they had driven out the Gauls, who formerly had dwelled there. And that these were the only men who in the days of our fathers, all Gallia being sorely troubled, had prevented the Teutones and Cimbres from entering within the bounds of their territories, after which it came to pass that the memory and record of these famous deeds have made them proud and conceited because of their great power and skill in martial affairs, {1601L, not in 1602G{[as mentioned in] Suetonius in Tib. 9. In the German war, he sent over 40,000 volunteers into Gallia}1601L}.

198.10. In the 8th book of Cæsar's Commentaries {not in 1606E{by Hirtius}not in 1606E} [we find] The Belgæ, whose courage was great}not in 1602G}.

Strabo, in the 4th book {1606E only{of his Geography}1606E only} says The Belgæ wear cassocks or cloaks, their hair [is] long and they wear side breeches. Instead of coats or jerkins they use a kind of sleeved garments, hanging down to their waist or as low as their buttocks. Their wool is very coarse and rough, yet has been cut close to the skin. Of that they weave their coarse, thick cassocks which they call lænæ, rugs or mantles.